In L4. The Magic Circle Jango instructs Jay to eat a hallucinogenic centipede, in continuation of all the phallic imagery we’ve seen so far. Back when Jay smoked powdered centipede he woke up in the afterlife. Now he’ll experience the centipede’s full potency, but that’s a reveal for next week.

In this section Jango reveals that the mysterious masked figure, Virgil Blue, is just a pile of robes around a centipede bush. The real Virgil Blue retired decades ago in the same manner as every person to take the mantle of Blue: walking above the Sheridanian clouds never to return.

This explains why Virgil Blue never speaks or moves. It doesn’t explain why their silent speeches are so engrossing, or how they spoke to Jay, but I’m happy to chalk it up to magical realism. (Alternatively, maybe just smelling centipedes can give you a contact-high. Jay was in an enclosed space with the Virgil for an extended period before he heard the mask speak.)

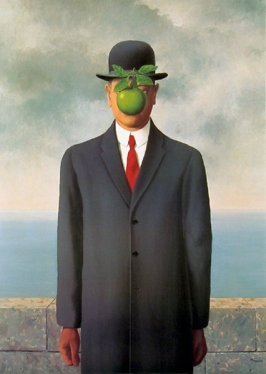

J. J. Abrams, the mind behind LOST and the Cloverfield franchise, has a narrative idea called a mystery-box. A story keeping a secret can engross its audience; just owning a box with a question-mark on it “represents infinite possibility,” says Abrams. “It represents hope. It represents potential.”

Compare this to the idea of “the magic circle.” Says Dutch historian Johan Huizinga, quoted from this Wikipedia article,

All play moves and has its being within a play-ground marked off beforehand either materially or ideally, deliberately or as a matter of course. Just as there is no formal difference between play and ritual, so the ‘consecrated spot’ cannot be formally distinguished from the play-ground. The arena, the card-table, the magic circle, the temple, the stage, the screen, the tennis court, the court of justice, etc, are all in form and function play-grounds, i.e. forbidden spots, isolated, hedged round, hallowed, within which special rules obtain. All are temporary worlds within the ordinary world, dedicated to the performance of an act apart.

Fiction is a space where literally anything can happen. Many fictional worlds follow certain rules for the sake of narrative consistency, but these rules are largely self-enforced by the storyteller and often disagree with the rules of our reality. When we engage with a story, we cross into a magic circle and accept an alternate mode of existence.

In this context, a mystery-box is a rule in a narrative reality which is hidden from the audience, but which impacts the story. The audience is left to speculate at the hidden aspect of the narrative reality until the eventual reveal.

An unfortunate drawback is that if the reveal of a mystery-box’s contents contradicts the established rules of the fictional universe, the audience might retroactively judge the earlier parts of the story. They’ll say, “you didn’t actually have a plan at all—you just enticed us with the idea of a satisfactory answer.” Perhaps worse is a mystery-box whose contents don’t live up to the expectations. I don’t mean to pick on J. J. Abrams, but I recall people being disappointed with the ending of LOST for technically explaining everything but with a narrative “meh.”

So when I reveal something, I hope it answers the reader’s questions in a way which makes them more engaged with the story, not less.

This section of Akayama DanJay opens a mystery-box with the removal of Virgil Blue’s mask. Virgil Blue being a centipede bush answers some questions (why are they immobile? why are they silent?) while raising others (why is the mask so engrossing? why did Jay hear the story of Nemo?), which I hope encourages readers to come up with their own answers and imbue the imagery with thematic meaning.

If Virgil Blue’s silver mask represents Truth as solid as the moon, then the reveal of centipedes implies that Jay’s hallucinations will reveal the Truth of Akayama DanJay. We’ve seen Dan. We’ve seen Jay. Now that’s see Akayama’s side of things.