(This is part 4 of a story about an ultra-marathon-runner who makes a million-dollar bet that he can beat a billionaire on horseback in a hundred-mile-race. The ultra-marathoner will soon learn that without a million dollars to lose, the billionaire will demand his legs.)

2019

BEEP. BEEP. BEEP. BEEP.

Kevin turned off his alarm-clock. It was ten in the morning. He slumped out of bed and started a pot of coffee.

As the coffee dribbled, Kevin checked his Facebook, his Instagram, and his Twitter. He smiled; he’d doubled his followers since Jonas’ book came out. What was the title? Live to Run? Kevin would never bother reading it, but apparently he came across quite well. He’d have to thank Whitney for the publicity.

Kevin checked his texts and almost dropped his phone. “Jonas! You idiot!” He dialed a number and put the phone to his ear. “Whitney! Your ex is making an ass of himself again! Call your Uncle Hermes, I’ll pick you up.”

BEEP. Mile 31: 8:04 / 4:10:22.

The maps said there was a river running down this side of the mountain, and technically, there was, but I hesitated to fill my three-liter water-backpack. The water flowed crystal clear from a rusty industrial pipe. It never occurred to me that this river might be man-made, and chlorinated, or worse.

Anyway, I filled up my three-liter backpack and tossed in a water-purification tablet. The backpack sloshed every step. After half an hour bouncing on my back, the water might be drinkable. I crossed my fingers; I couldn’t run seventy more miles without water.

On a typical ultra-marathon there’d be regular stations where runners could load up on supplies, or seek medical attention, or even quit the race. Some ultras over hundreds of miles were just lots of loops around small courses, so runners passed one aid-station over and over. A runner might even have a partner, a ‘pacer,’ who could carry things like a squire for a knight.

I was Whitney’s first squire.

BEEP. Mile 32: 7:32 / 4:17:54.

She’d signed up for a fifty-miler by the beach. We’d planned it for months. I’d be at each aid-station every ten kilometers. After thirty miles I’d be allowed to run beside her and pace her for the rest of the race.

Her Uncle Hermes taught me the rigmarole of race-staffing. He was an old hand at ultras. “Here, Jonas, hydro those guys.” At a marathon I might hold out a paper cup of water for the racers every mile. At the ultra I filled up a guy’s water-backpack while he puked into a bush. His stomach-capacity impressed me; he was skinny like a skeleton, but hurled up whole pints. Hermes pat him on the back and offered him some pretzels. “Whitney should be here soon,” Hermes told me. I wondered if she’d be as gaunt as most of the people who’d already passed.

“Hoy!” Whitney waved as she came around a cape. She was exhausted but jubilant. She tossed me her water-backpack. “Fill ‘er up and put ‘er on!”

Hermes untied Whitney’s shoes while I filled her water-backpack. I turned the backpack upside-down so the air-bubble floated to the top, where I could suck it out the hose. That’d keep the backpack from sloshing every step. “You’re the seventh woman overall,” I said, “and fourth in your age-group.”

“Am I on pace?”

“Perfectly.” I donned Whitney’s water-backpack to carry it for her while Hermes finished retying her shoes. If Whitney had crouched to tie them herself, she risked cramping and collapsing. “Let’s go.”

BEEP. Mile 33: 7:27 / 4:25:21.

It was fun to work pit-stops for Whitney, and I treasured running beside her when she was already fatigued. After she’d run thirty miles I could actually keep up with her, and I felt useful pacing her to the finish-line in ten hours. She ran the last mile in eight minutes, then kicked off her shoes. Her toenails were black and bleeding. We collapsed together near the ocean and let waves lap at our legs.

Then she asked, “when are you doing one?”

So I was obligated to let Whitney pace me on a 50-miler. And let me tell you, she looked different after I’d run thirty miles.

She was like peanut-butter: on a long run, I couldn’t get enough. When Whitney ran beside me, my body demanded her. She was salt and sugar and oil.

That’s why I signed up for a 100-miler. I was eager to speedball my girlfriend when my body was battered and bruised. “Are you sure?” she’d asked. “My Uncle Hermes ran few hundos back in the day. He says it’s a whole new world of pain.”

“Running is all about suffering,” I’d said. “The one who suffers best is the one who wins.” And boy, did I suffer. I ran from sunrise, to sunset, to sunrise, and Whitney was an irresistible siren luring me on when I wobbled.

BEEP. Mile 34: 7:44 / 4:33:05.

That hundred-miler was at a national park in the Midwest. About twenty-two hours in, I saw a bird I didn’t recognize. “Whitney?”

“Need water?” She offered me the hose from her water-backpack.

“No, the bird.” I pointed at the sky, near the sun. “Look. A big red bird.”

“There’s no bird, Jonas.” Whitney shook her head. “You’re hallucinating. Hermes warned you this would happen eventually.”

“Huh?” I couldn’t believe it. The bird looked real as anything I’d ever seen. “It’s right there, though. You must see it, it’s huge. It’s got a wing-span like a semi-truck.”

“Does that really sound real to you?”

“I guess not.” The bird dissolved into clouds. “Maybe I should quit now and take the DNF—‘Did Not Finish.’ Hallucinating doesn’t seem healthy.”

Whitney puffed as we jogged uphill. “You can stop at the next aid-station if you want, but you’re just a few hours from the finish. Hallucinations can’t hurt you, Jonas.”

“I… I don’t know.” I wondered which rocks and trees were real or not. “I don’t know.”

“Look. Jonas. Look at me.” Whitney pulled off her sports-bra. “These are real. These are right in front of you.” I drooled. “Keep running.” I could only obey.

BEEP. Mile 35: 7:21 / 4:40:26.

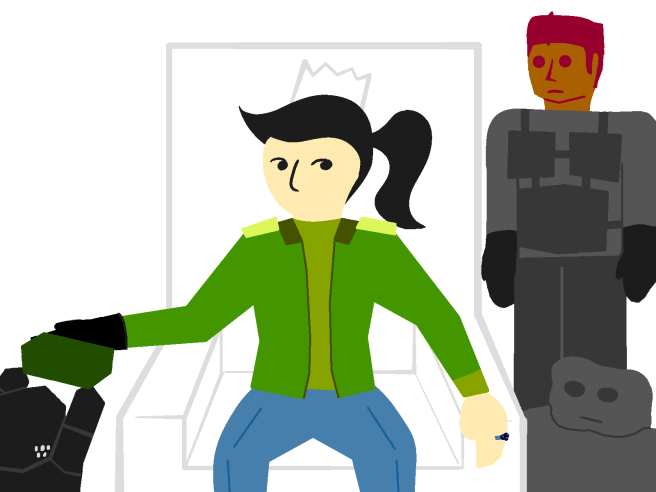

Kevin rolled down the driver’s-side window. “Hey! You! Open up the gate.”

A security-guard sitting in a booth crossed his arms. He wore a leather jacket and sunglasses. “No one gets onto the Bronson Estate without permission.”

“Call Alphonse. He’s gotta be expecting us.”

“Lemme see your ID.” Kevin gave the guard his driver’s license. “All of you.” Whitney gave the guard her license, too.

“I don’t have an ID, man,” said Whitney’s uncle Hermes. “I try to stay off the grid.”

“Then look at the cameras, sir.” Hermes noticed a security camera on each side of the wrought-iron gate into the Bronson Estate. The security guard returned their IDs. “I’ll tell Mister Bronson you came, and you can schedule an appointment. Mister Bronson doesn’t want to be disturbed today. He’s on important business.”

“So are we,” said Whitney. She sucked the air-bubble out of a water-backpack. “Could you please contact Alphonse? I think he’ll want to let us in.”

“No dice.”

BEEP. Mile 36: 7:51 / 4:48:17.

I sucked water from the hose of my three-liter backpack, then spat it out. It tasted bitter. The water Alphonse pumped up the mountain was chemically treated to look pretty. No wonder there was barely any wildlife in the Bronson Estate besides rodents, lizards, bugs, and birds. Fish weren’t welcome. A deer stranded here would die of thirst.

And so would I. I hadn’t had a drop of water in six miles. My mouth was dry. I couldn’t keep this up. I didn’t stand a chance.

My phone rang.

I pulled it out of my backpack. “Hello?”

“Jonas, you idiot!”

“Hi, Kevin. I guess you got my text. I’m racing the horse as we speak.”

“Jonas, I’m here too.” It was Whitney. “We’re outside the Bronson Estate.”

“Oh… I’m sorry you came all this way for me.” I wiped tears off my cheek and licked them off my palm to conserve water. “I need supplies, guys.”

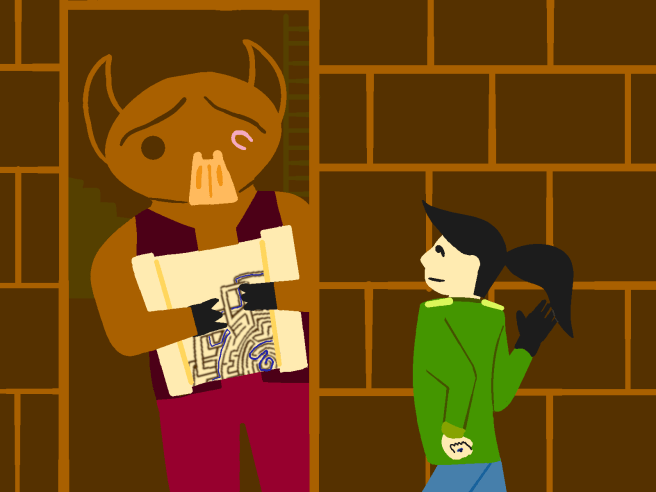

“We’ve got all you need, Jonas,” said Uncle Hermes. “We’re gonna get you through this. But there’s something you’ve gotta do.”

“Okay. What?”

BEEP. Mile 37: 7:43 / 4:56:00.

“I just heard your GPS-watch beep,” said Whitney. “Are you using the running app I introduced to you? Do you have a premium membership?”

“No. I’m still bumming off your premium membership.”

“Perfect. I’m logging in on my own watch,” said Whitney. “Alright, I’m monitoring your run live. We can track your GPS-location and meet. I see you’ve got an eight-minute-mile average so far. Not bad. You might actually do this.”

“Jonas, they’re not letting us onto the estate without permission,” said Hermes, “but they won’t call Alphonse to ask if we can come in. Can you make him open the gate?”

“Uh…” I looked at the horizon. “I don’t know. He must be miles and miles ahead.”

“Catch that horse, Jonas,” said Whitney. “We can’t help until then.”

Kevin hung up. I tucked the phone back into my backpack.

BEEP. Mile 38: 7:21 / 5:03:21.

Whitney’s voice rejuvenated me. I felt her assessing my form from afar.

This was possible. I had a chance. I just had to catch the horse.

My blister was bigger than a half-dollar. Each step, I stomped my right foot until the blister popped and soaked my sock with warm fluid. It hurt—it burned like a salted wound—but now it wouldn’t mar my stride.

Whitney, Kevin, and Hermes. What a nice reunion. I’d texted only Kevin about racing the horse because I didn’t think Whitney cared for me anymore, but I suppose texting anyone about my dumb decision was just a cry for help. “Help, I’m going bankrupt staring at a horse’s ass!”

But what an ass.

And there it was.

Champ and Alphonse were stopped by the side of the trail halfway down the mountain. No wonder I hadn’t seen them from above—I’d assumed they were twenty miles passed, not waiting for me just ahead.

“Jonas! Good to see you.”

“Alphonse,” I panted, “What are you doing here?”

“You’ve got the advantage now!” Alphonse cheekily displayed a band-aid wrapped around his middle finger. “I endured an injury a few miles ago, when Champ brought me too close to a tree branch. I hoped to hold out until mile forty, but I fear I must throw in the towel here.”

BEEP. Mile 39: 7:32 / 5:10:53.

I slowed to linger beside him. “You mean… you give up?”

“No, no—My best jockey is tapping in! She’s arriving here by helicopter. She’ll ride Champ in my stead. Thirsty, Jonas? Catch!”

He tossed me a plastic bottle of water. I walked a few steps to drink two-thirds of it. “You can’t switch out. This race is between you and me.”

“Actually, if you read the contract you signed, you’re racing the horse, not me. The jockey is irrelevant.”

I locked eyes with Champ. The horse flared its nostrils. Alphonse’s spurs had bloodied Champ’s ribs. “My crew needs your permission to enter the estate, Alphonse. Can you let them in?”

“I’ll see what I can do,” said Alphonse, “but we have something to discuss. It’s come to my attention that you lack funds for our wager. If you lose, you can’t afford to pay up.”

“Really? Gosh.” I feigned surprise and jogged away. “I’m sure your people can talk this over with my people, once you let them in.”

Alphonse jogged after me. His spurs clattered every step. “I’d rather talk to you directly. I want to propose a deal.”

“What kind of deal?”

“Let’s call it…” Alphonse laughed. “Charity! If Champ wins, you’ll make a donation within your price-range and we’ll call it even.”

I tried running faster to leave him behind, but while I followed the trail around back-to-back switchbacks, Alphonse cut corners to keep up. “A donation? To who? How much?”

“Nothing you can’t afford, and for a noble cause. You might know that the Bronsons have significant holdings with wings of the medical industry.”

“Horse medicine, or human?”

“Both! If you lose, I’d just ask you to provide a sample for the labs. I’m sure they could learn from your impressive physique.”

“What do you want? Like, a spit sample? Blood?”

“No, no, Jonas.” Alphonse covered his mouth to hide giggles. “Jonas, I want your legs.”

“…Huh?”

“Your legs, Jonas. I value your legs at one million dollars, and accept them as your ante. If you lose, in lieu of one million dollars, I will take ownership of your legs.”

“Like… cut them off?”

“For medical purposes! And remember, only if you lose.”

“I can’t accept that. No one could.”

“Jonas, Jonas. If you win this race, you expect me to pay up, right? It’s only fair you keep your end of the bargain and put something at stake. You must restore the bet to make up for your deception. I can’t forgive you otherwise.”

“No deal.”

“You should really consider my generous offer. Remember, you’ve run almost 40 miles on my private property; at my standard rate of $10,000 a mile, you already owe me about half a million! You’ll ante both legs, or we stop the race here and now and I’ll settle for just one of your legs, or both legs below the knee.”

I was about to say I’d shove a leg, or both legs below the knee, right where the sun didn’t shine, but then I heard distant whirring helicopter blades. I was ahead of the horse, and would be at least until the new jockey arrived. For the first time in this whole race, I had the advantage. I couldn’t physically bring myself to turn down the wager. “Okay,” I whimpered. “I’ll take the bet.”

“You mean it?” Alphonse laughed and clapped. “I’ll call the front gate and let your crew into the estate. Oh, what fun!” He finally stopped following me. I left him and Champ behind.

BEEP. Mile 40: 9:13 / 5:20:06.

I plucked the red flag at the fork and tossed it toward the trail to the right. That trail was rocky and narrow, and I hoped a horse would have trouble with it.

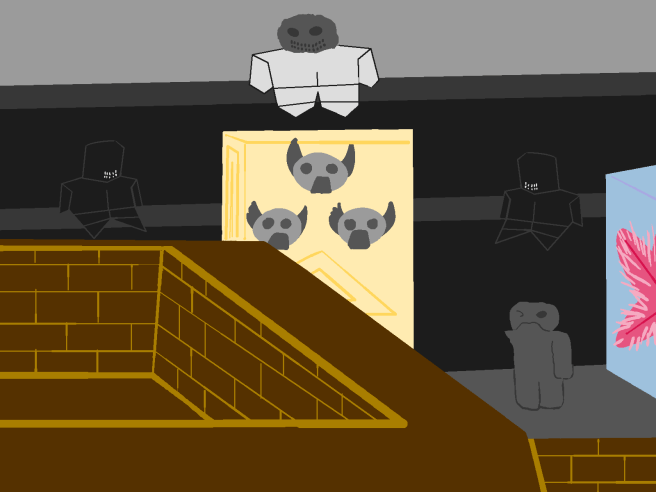

2012

“And the winner is…”

Father Bronson’s coughing drowned out the announcements. He sounded like he’d hack up his last lung. Alphonse pointed to the stadium’s sparse spectators. “Look at all those winners, Dad!” Men in expensive suits cheered or tore up bad bets.

“Where did—” Father Bronson coughed again. He gripped the wheels of his wheelchair to hork up phlegm. “Where did you find these people?”

“They’re colleagues, and colleagues of colleagues,” said Alphonse. “None of them is worth less than a billion bucks, and they relish the thrill of putting millions on the line. I truly have the people’s support!”

The gates at the finish-line slammed shut before the last horse. Their jockey howled and shook the reins until a dart shot him in the neck. The jockey fell from the saddle, unconscious.

Six men in leather jackets led the horse into a big metal box, and tossed the jockey in afterward.

“Son, what’s happening?” Alphonse shushed his father.

The six men turned a heavy iron crank. Horse-glue poured from a spout into a bucket. The spectators cheered.

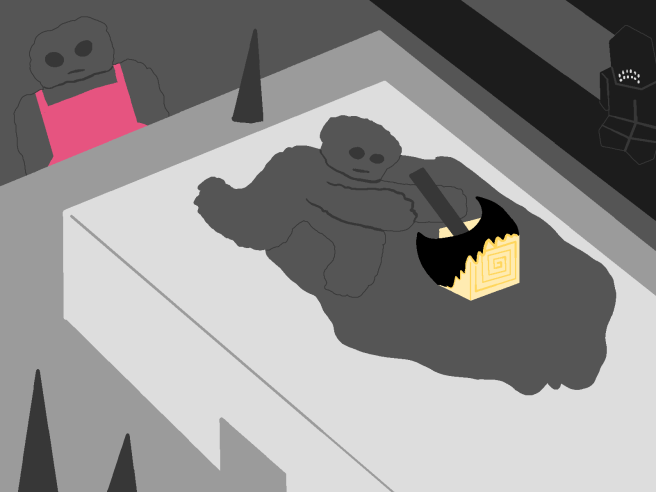

A woman in a white lab-coat and rubber gloves led two men carrying a white cooler to the big metal box. She opened a drawer on the box, where her two men retrieved another cooler full of eerie lumps. “Organs!” said Alphonse. “Even a losing jockey’s organs are economically valuable. Think of how many lives we can save with transplants, and how much we can charge!” While her two men loaded the box’s drawer with the empty cooler for the next race, the woman with the lab-coat withdrew a syringe from a panel on the box. She brought the syringe to Alphonse. “Look, dad!”

“What is that?” asked Father Bronson. “Hey, don’t!”

Alphonse relented and didn’t yet inject his father with the syringe. “Once we’ve extracted every organ with medical value, there’s chaff leftover. Our labs have perfected a technique to turn that chaff into a nutrient-paste. It’s a cure-all! Don’t you want to walk again, Dad? You could even ride a horse!”

Father Bronson blanched, then rolled the wheels of his wheelchair to turn away. “Son, I don’t think you’ve understood the finer points of my advice. My enemies in the media may disagree, but even I have standards, and what you’re describing is beneath me.”

Alphonse struggled for words. “Oh. I get it. This is the jockey that came last. I can’t inject you with a loser. Your blood is too royal for that.”

Father Bronson opened his mouth, but decided against the rebuke he had in mind. “I’m leaving, son. Contact me when you’ve made something of yourself.”

As his father wheeled away, Alphonse shook. He took a minty metal toothpick from the breast pocket of his gaudy military jacket and suckled it. “You, Doctor,” he said to the woman in the lab-coat, “bring me the jockey who won that race.”

“In a syringe, you mean?”

“No, just send them over.”

The doctor walked to the finish-line and addressed the winning jockey. The winning jockey didn’t get off her horse; she rode it to Alphonse’s track-side seats. “Howdy, boss.”

“Congratulations.” Alphonse tossed her the syringe. She cringed, but caught it carefully. “That’s a month of medical care in a hypodermic needle. Good for what ails you.”

The jockey smiled. “I appreciate it, sir, but you already pay all my medical expenses.”

Alphonse cocked his head. “Huh?”

“When I was a kid, I came second-to-last in a charity race, and since then you’ve funded my healthcare. Thanks to you, I’ve got the best wheelchair on the market.” She pat her horse.

“Oh.” Alphonse shrugged. “Well, with that injection, you won’t even need a wheelchair for a while. You’ll be able to walk. I’ve seen lab-rats with terminal illnesses get a new lease on life.”

The jockey inspected her new syringe. “If I come first again, will you give me another?”

Alphonse laughed. “Let’s make a deal.”