(This is part five of an ongoing series starting here. Our story so far: Aria Twine has led her minotaur, Homer, to become one of humanity’s royal commanders. Now he’ll have to beat seafolk at the board-game which determines the fate of nations.)

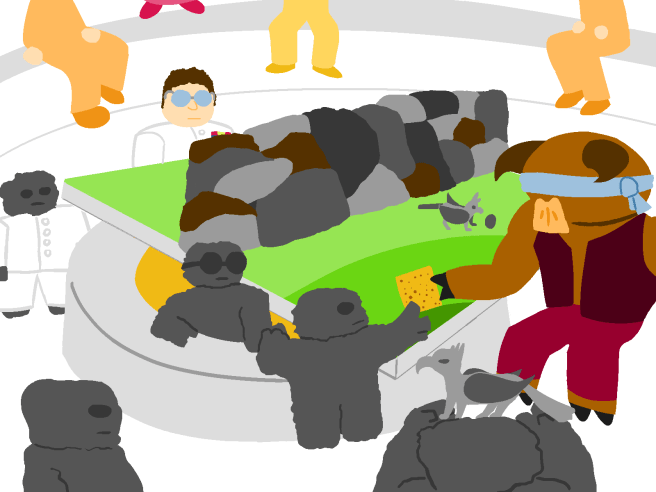

Homer’s sweat dripped through his fur like tiny, salted streams. He adjusted his dark goggles to block out the fiery summer sunlight.

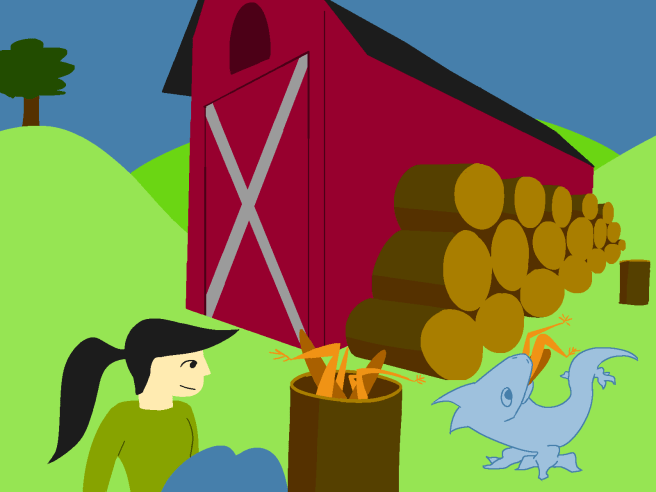

Despite the heat, a circle of snow suffocated the dry grass. The still air became a frozen gust when Scales the ice-dragon exhaled. It wore armor like transparent glaciers. Its wings were fifteen feet from tip to tip, dangling icicles.

“Good boy, Scales! Good boy,” cooed Aria. The royal beast-master lent her a thick glove to pat her dragon’s muzzle. “He’s still on elvish fodder?”

“Yep. A barrel of crickets a week.” The beast-master scratched his scar. “This guy’s bigger at six months than most dragons I’ve seen at five years.”

“Is he spitting ice yet?”

“Hoo yeah. Every morning.”

The dragon puffed mist from its nostrils. “His frosty breath could be handy against seafolk.”

The beast-master shrugged. “You don’t see many dragons in table-war ‘cause they usually fly for the wild wastes as soon as their wings come in. If you wanna use Scales on the table, make sure the map’s far from the wastes, or his game-piece will escape. It’s no good keeping the dragon in our stables if its game-piece is bust.”

Aria nodded while checking the dragon’s eyes: light blue, clouded like cheap crystal balls. “I need exclusive rights to this dragon’s brass. Don’t let the other humans in the tournament use it.”

The beast-master cocked his head. “Aren’t you dead, Aria?”

Aria corrected herself: “Homer, the minotaur, needs this dragon’s brass.”

The beast-master called his gnomes and they waddled over to take Scales’ measurements. “Good luck,” he said to Homer. “Against seafolk, you’ll need it.”

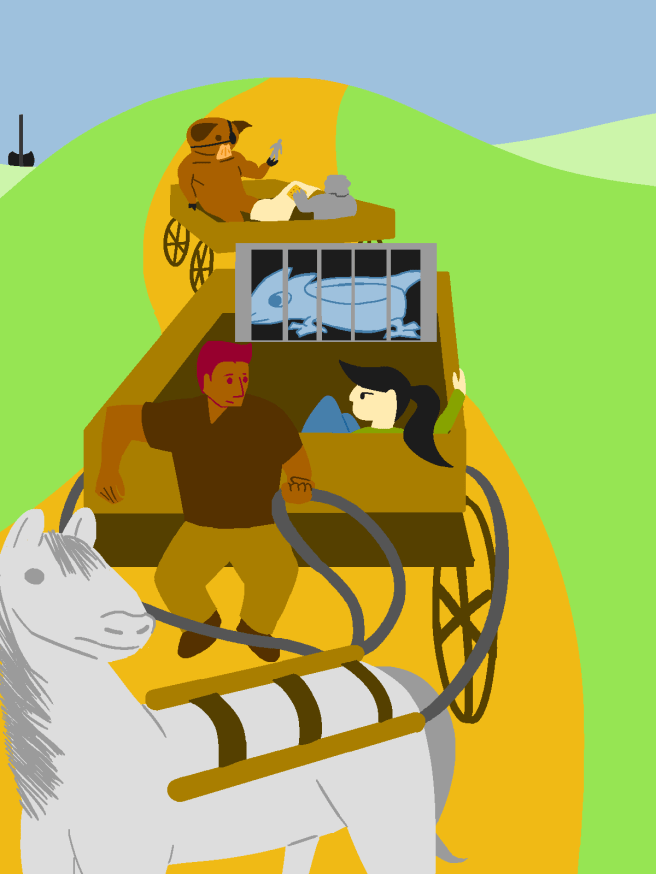

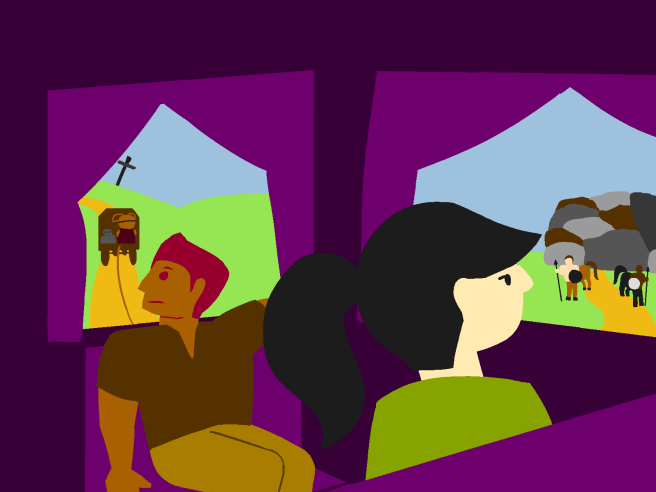

“I’ve never been to the wild wastes,” said Sir Jameson. The Great Sword sank behind hills in the carriage’s back window. “I’ve never left human territory, actually.”

Aria squinted skeptically at the centaurs’ border wall. “When I was a royal commander, I’d be carted across the wastes every week to fight elves and dwarfs. Sometimes we’d snag game-pieces on the way, to keep my brass collection unpredictable.”

“Game-pieces?” Jameson frowned. “You mean animals?” Aria shrugged. “Watch your language around the wall,” said Jameson. “Centaurs won’t like being called game-pieces, and they’ll call your griffon a prisoner of war.”

“Relax,” said Aria. “We’ll deal with stuff like that once we’ve beaten the dwarfs. Oh! Hey there, Homer.” Homer easily matched the pace of the carriage on foot. “Are you and Quattuor feeling cramped in the second carriage?”

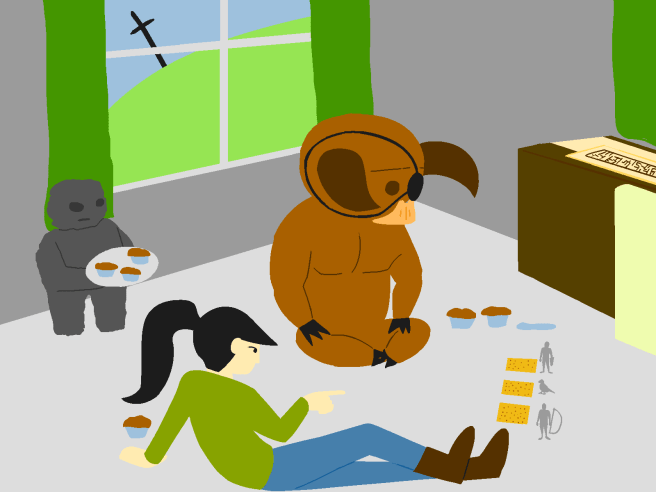

“Awks.” Homer mimed holding an object in both hands.

“You want your box? Jameson, help me lift this thing.” Aria and Jameson hefted a wooden box from under their seats. “Careful, Homer, these figurines are heavy!”

Homer held the box as easily as Aria might hold a single brass card. “Ow ong?”

“We’re a few days from the seafolk’s dock.” Aria massaged her fingers. “You’ll love it, Homer. Seafolk can’t resist putting on a show, and there’s all-you-can-eat shrimp.”

Homer gave a thumbs up.

The carriage-driver pulled his horses’ reins as they approached the centaurs’ wall. “Get back in,” he said to the minotaur, “and everyone, have your brass ready for inspection.”

“Brass?” Aria tapped her foot. “But my brass says that I’m dead.”

“That won’t matter,” said the carriage-driver. “You’ll see why. I’ve made this trip before.”

Aria heard hoof-steps as centaurs approached the carriages. Two interrogated the carriage-driver, and another poked his nude torso into the carriage’s side-window. “Brass, please.” She and Jameson gave their brass identification cards to the centaur, but he declined to take them. “Those look like brass to me. You’re good to go!”

Beyond the wall humanity’s rolling hills gave way to desert, and across a river the desert gave way to mountains. Then thick forests buzzing with black beetles blocked the way, forcing the carriages to trek through tundra slick with ice to reach flat, black sheets of volcanic stone. A distant plume of dark smoke rained ash.

“I feel magma,” whispered Quattuor. He spoke up so Aria could hear him in the front carriage. “Ms. Twine, I request a stop to confer with the gnomish core for news.”

Aria leaned out the carriage window. “Driver, can you take us where the smoke’s coming up? Quattuor wants a lava-bath.”

The carriage-driver hesitated. “Lava spooks horses. This is as close as I’ll get.”

“Sounds like you’re walking, Quattuor.” The gnome stepped from the carriage and marched toward the plume of smoke. Aria tested the dark rock with her boot before stepping off the carriage. She arched her back to crack her spine. “Just a little longer to the docks, Homer.”

Homer pointed in the four cardinal directions to four different micro-climates.

“Yeah, the wild wastes are sort of a biome quilt,” said Aria, “and it’s never the same from month to month. You know why?”

He shook his head.

“Elves, forests. Humans, hills. Seafolk, saltwater. Land changes for those living there. That’s why seafolk can’t own property above sea-level: they’d salt up wells just by proximity. But there are so many monsters in the wild wastes, and they move around so much, the land is a patchwork mess. I’m not sure how dwarfs affect the land.” She spat on the ground. “They just eat whatever’s underneath them. Homer, has Quattuor taught you how this tournament works?”

The minotaur nodded. “Ah iddle.”

“A little,” repeated Aria. “We’re holding a tournament to find the best commander to fight the dwarfs. When you fight Ebi Anago, the gnomes will award both of you up to five points based on performance. Then the gnomes pair people with similar point totals for round two. Think you can pull off a five-point match?”

He nodded again and pointed near the smoke. Their gnome returned shiny, white, and dripping magma. “Guaddorr.”

“Quattuor. Any news?”

“Queen Anthrapas has assigned her remaining tournament seats,” said Quattuor. “Harvey, Jennifer, and Thaddeus join Homer in representing humanity. Harvey and Thaddeus are fighting elves in the first round. Jennifer will join us on the dock to fight seafolk.”

“Perfect,” said Aria. “Homer can outscore those kids no problem.”

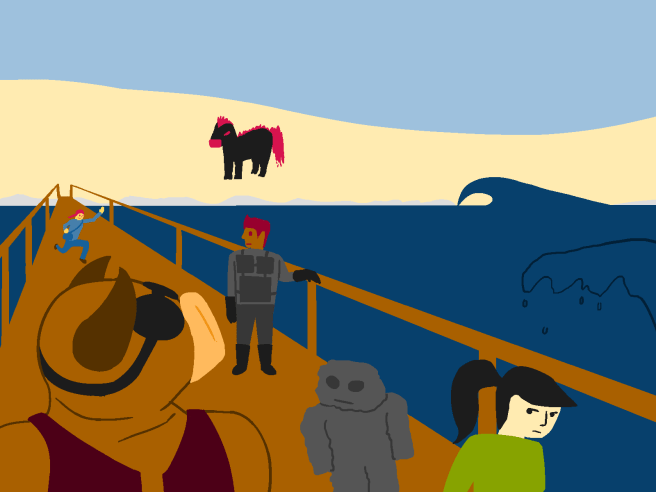

For the first time ever, Homer filled his chest with salty sea breeze. Waves fifteen feet high curled and crashed on white sand. A wide wooden dock stretched into the blue horizon. Sir Jameson’s gauntlet gripped the dock’s wooden railing like the boards beneath him might snap. “I’ve never trusted seafolk.”

“At least elves have legs,” agreed Aria. “You never know if seafolk are two steps behind or ahead.”

“I wonder what Jennifer thinks of them,” said Quattuor. “Here she comes.”

A sturdy black steed approached the dock. The mare’s mane stood on end like a trail of fire at night. Its nose twitched and unleashed a steamy cloud that enveloped its rider as she dismounted. She was about eighteen with red hair tied in a braid. She quickly spied Aria and sprinted down the dock after her. “Oh, great,” said Aria. “She’s a fan.”

Homer sniffed. Behind the scents of salt and fish he smelled ash and cinders. Jennifer’s horse waited patiently on the coast. Around its hooves, sand sizzled into glass.

“Aria Twine! Humanity’s path to victory! It’s an honor to meet you,” said Jennifer with a deep bow. “How’d you teach a minotaur to play table-war like that?”

“Where’d you learn to ride a Night Mare?”

“Oh, I’ve studied horses for years! Inspired by you, of course.” Jennifer jogged to keep up with Aria’s quickening pace. “I’ve read all about how you won matches with awesome animals! You changed the whole meta-game!”

“Nice to hear,” said Aria.

Jennifer clapped. “Can you tutor me?”

“Ha, no.” Aria pointed to Homer. “I’ve got my hands full.”

Jennifer’s smile sunk. Homer waved to her. “Well, can you autograph something for me?” Jennifer opened her purse and dug through brass cards to produce one wooden hobby-card.

Aria recognized it by sight. “That’s a hobby-copy of my old brass, isn’t it?”

“I used to play with it all the time!”

Aria finally smiled. “Okay, I’ll sign it if you teach my apprentice about seafolk.”

“Oh.” Jennifer looked at Homer, who watched her behind dark goggles. “Deal.”

“Great. Get talking.” Aria swerved to put Jameson and Quattuor between her and Jennifer. Jennifer pursed her lips and turned back to Homer.

Homer’s face wasn’t built to smile, and his best attempt was a sickly grimace. “Heddo, Edafrr.”

“Hello? Was that hello?” Jennifer sighed. “You know, some of Anthrapas’ commanders are cross with you. Tournament seats were tight as they were, and you took one of them.” Homer shrugged. “But anyway, have you fought seafolk before?” He shook his head. “Really? The egg thing you pulled on Harvey seemed like a seafolk trick. How many official matches have you played?”

Homer scratched under his chin. “Doo.”

“Two?” Jennifer almost tripped. “You’ve played table-war just twice?” She folded her arms. “Well, seafolk is a catch-all term for sentient creatures from the ocean. They’re rich, because the war against demons submerged most of the planet’s land-mass. They’re so rich they paint all their figurines in true-to-life color!”

The end of the dock came into view; wooden benches formed a semicircular theater facing the empty ocean. A sizable audience was already present.

“Seafolk are great at table-war, partly because they can buy the best game-pieces, but also because they don’t think like us. I’ve seen seafolk bring a warship to battle on a landlocked map. When the match started they toppled it to use as cover! The seafolk said, afterward, he didn’t even know what a boat was.”

“Hm,” mumbled Homer.

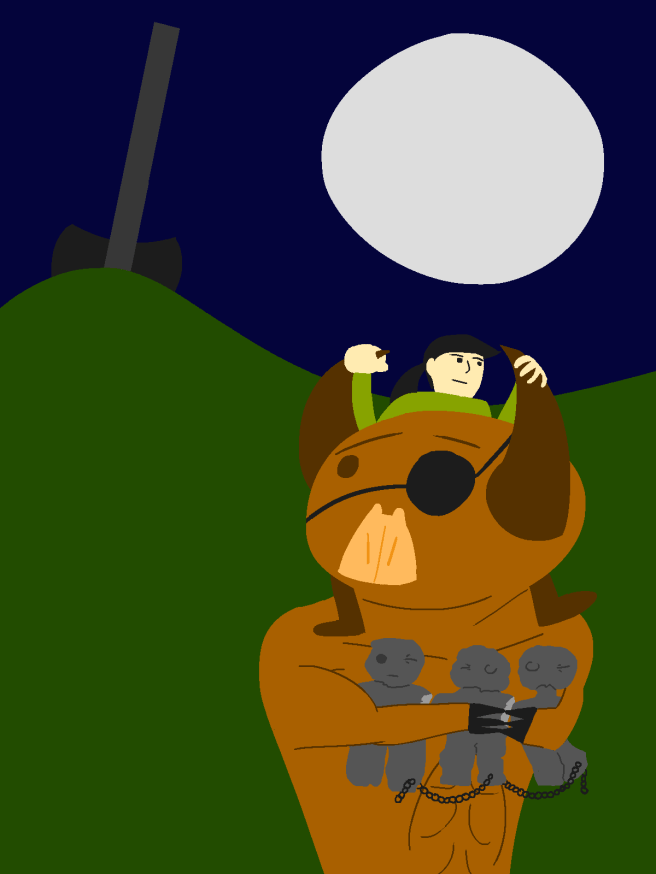

At the end of the dock, Aria made Homer lie on a bleacher in the front row. “Your game’s after sunset. Rest until then.”

The elves in the audience took turns diving into the ocean, screaming and cheering, then climbing back onto the dock to dry off. Homer knew elvish ambassadors were chosen by height, not political savvy, but they should have known to keep quiet when someone was trying to nap.

Nonetheless Homer managed to fall asleep. He woke after sunset to gravelly voices:

“Minotaur.”

“Look. Scars.”

“Missing an eye.”

Homer pretended to stay asleep. He sniffed the dwarven odor of carrion and crushed rocks. He heard the clinking of their full-body armor.

“Missing an eye, but good at table-war.”

“Kill it?”

“Gnomes would kill us with demons.”

“Let gnomes kill us if death means victory for dwarfs.”

“If we’re lucky, gnomes would kill us. If we’re unlucky, the Mountain Swallower would take us.”

The chills down the dwarfs’ spines were so intense, even Homer shivered. “Mountain Swallower worse than death.”

“Just watch the minotaur.”

“Agreed.”

The dwarfs sat two rows behind Homer. Homer yawned and sat up. He saw Aria and Jameson talking to gnomes in the bleachers.

“Oyster, sir?” A gnome offered Homer a platter. “Shrimp and oyster, all ocean-fresh, courtesy of Emperor Shobai.” Homer took a shrimp. It had beady black eyes.

“Take as much as you wish, sir.” The gnome wore shells and jewelry. “I am Emperor Shobai’s official translator. I will assist in the games tonight. Please find me if you have any questions.” Then the gnome left to offer seafood to elves. “Oyster, ma’ams?”

Aria snatched an oyster as she strode to Homer’s side. “Rested up?” she asked. “We’re in for a show. Shobai’s fourth wedding is tonight.”

“Eddin?”

“Didn’t you have weddings in your labyrinth?” Aria tilted her head back and drank the oyster. “It’s when people promise to stay together. Look, they’re starting!”

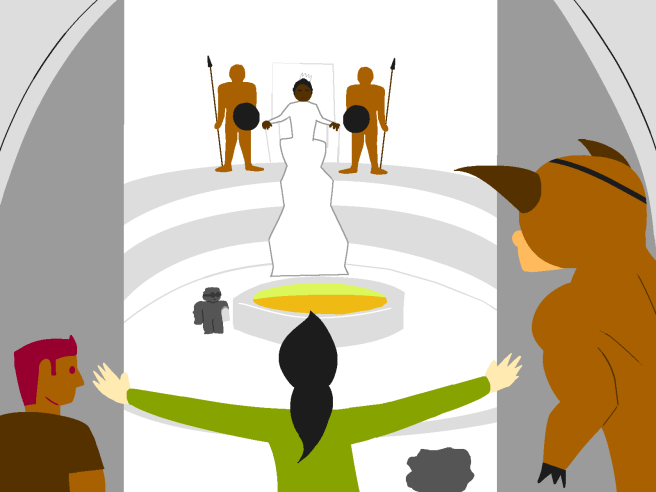

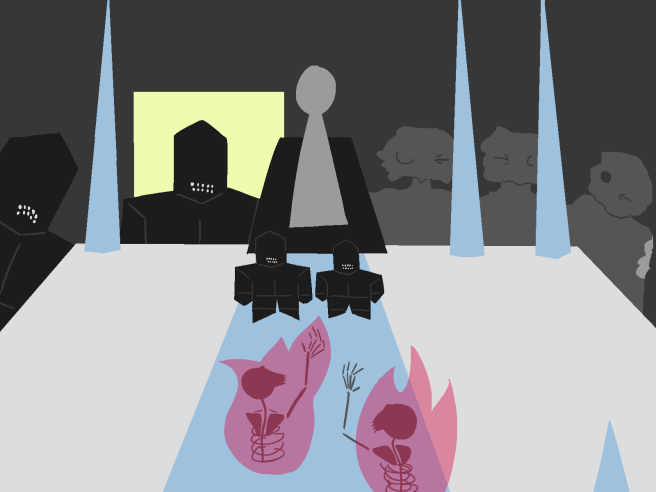

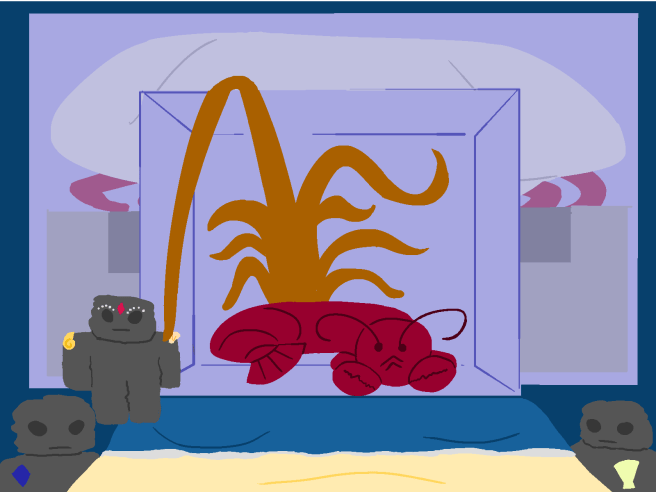

The ocean before them bubbled music like the calls of distant whales. A glass tank rose from the depths lifting enough water to fill a lake. Inside the tank was another semicircular theater packed to the gills with seafolk playing conch-like instruments. Most of the seafolk were eel-like with mouths gaping like goldfish. Other seafolk were more fishy, with long, finned tails. A few seafolk were unique, sporting tentacles or urchin spines or shells from which glowing tendrils grasped hungrily. Homer covered his ears as the music climaxed, then stopped.

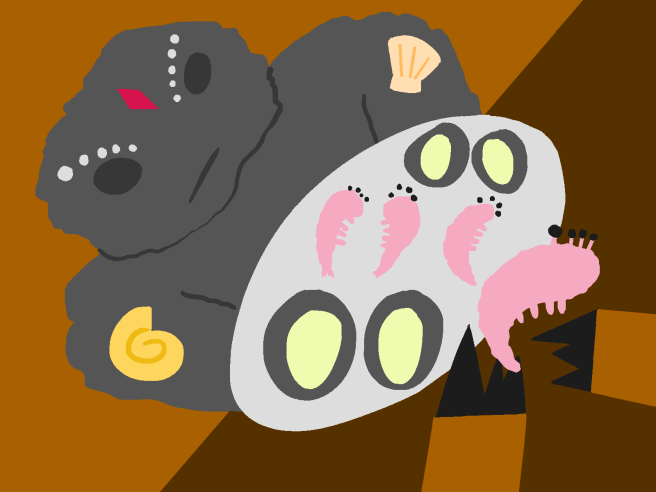

Bright bio-luminescent sparks lit the tank like fireflies, revealing the underwater emperor. Emperor Shobai was a clam fifteen feet across. From its hinge jutted ten gnarled crab legs twitching like red robes. Each segment was wrapped with gold rings.

The first stars appeared above the audience.

The official translator-gnome walked across the dock and raised his rocky hands. “Esteemed guests, Emperor Shobai extends his deepest gratitude for your attendance.” Behind him, the clam’s lips opened and closed. “We will keep the wedding short. Introducing the bride, Madam Kai Ba.”

A seafolk from the first row floated upwards. She wore a fluttery white wedding veil. The other seafolk lifted their instruments to blow haunting tones. Meanwhile, a second gnome joined the first on-stage. It wore a similar white veil.

Emperor Shobai opened his enormous mouth. Inside, three red tentacles three feet thick lifted the wedding veil with infinite care. Simultaneously, the first gnome unveiled the second gnome.

Madam Kai Ba was a seven-foot tall seahorse. Emperor Shobai retracted his tentacles and released bubbles. “Do you, Madam Kai Ba, take me as your husband?” translated the first gnome.

Madam Kai Ba released bubbles from her snout. “I do,” said the second gnome. “Do you, Emperor Shobai, take me as your wife?”

Shobai bubbled. “I do,” said the first gnome. Emperer Shobai slipped out a red tentacle carrying a golden conch on a silver cord, and placed it around his wife’s neck. “Let table-war commence!”

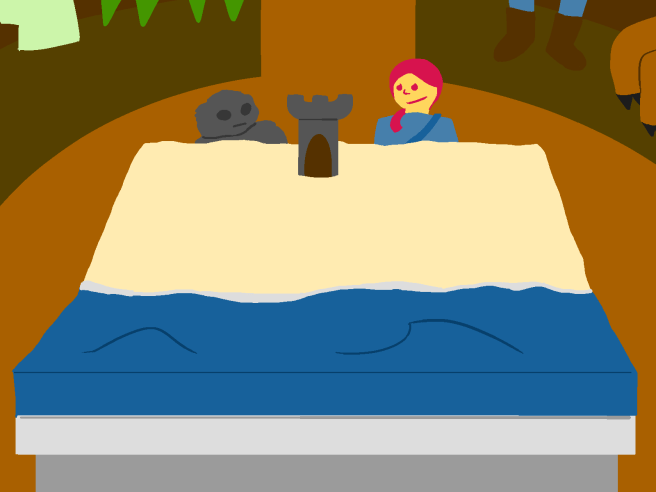

The seafolks’ tank moved back from the dock while gnomes set up the table. Jennifer’s side of the table was a sandy beach.

“Here.” Jennifer gave a gnome a brass card from her purse. This card was twice the ordinary length to accommodate a longer grid of dots. “I’m building this fort before the fight.”

“Have you the time and resources?” asked the gnome.

“Right here.” Another brass card changed hands. Gnomes constructed a tiny stone tower on the table. It had a wooden door.

Homer kept peeking over his shoulders at the dwarfs behind him. Their eyeless metal masks glared into his goggles. “Arra.”

“Hm?” Aria looked where Homer looked and saw the dwarfs. “Don’t worry about them.”

Homer struggled with consonants. “Oundain Salloer.”

“Mountain Swallower?” whispered Aria. “The Mountain Swallower is king of the dwarfs. A real piece of work. Oh, here comes Jennifer’s opponent.”

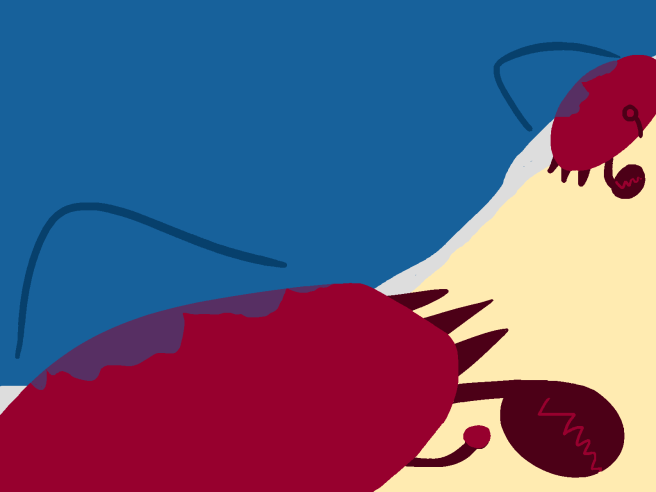

Another, smaller tank rose from the ocean between Shobai’s tank and the dock, opposite Jennifer at the table. A humongous sea star adhered to the tank wall with a thousand hydraulic suckers. A circular mouth of jagged teeth opened on its underbelly. The sea star’s side of the table was a turquoise ocean waving white foam against the coast.

“Sir Hitode will communicate hydraulically,” said the translator-gnome. He dipped his legs in the tank. The sea star wrapped the gnome’s legs with one of its five arms, and its hydraulic suckers puckered a message. “Sir Hitode welcomes Jennifer to the dock. He apologizes for keeping you waiting.”

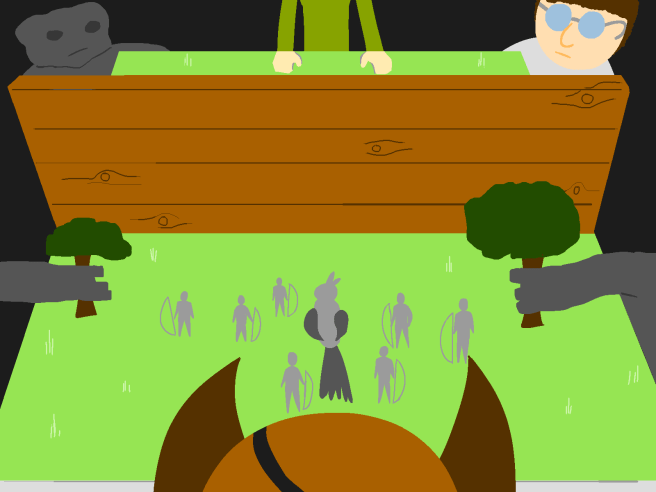

Jennifer trembled as Hitode sucked on the gnome’s legs to communicate secret commands. Hitode’s translator clacked fingers with another gnome, who put figurines under the model ocean. The faux water authentically hid Hitode’s troops.

On Jennifer’s side, two longbowmen manned her tower’s rooftop beside several barrels. Homer nodded; the tower’s interior could hide anything. Against seafolk, he’d decided, withholding information would be vital.

“Sir Hitode offers the first turn to you.”

“I decline.”

Five gnomes puppeted figurines under the model ocean. Two crabs crawled onto the coast; the figurines were the size of ordinary crabs, so the crabs they represented must have been meters across. The crabs dominated the left and right sides of the board. They left deep trenches where their abdomens scraped the sand.

“My longbowmen take aim.” Jennifer’s soldiers nocked arrows while the gnomes carved the crabs’ path to the tower. Only after the crabs advanced across two thirds of the table did Jennifer raise a hand to pause the action. “Open the tower.” The gnomes pulled open the tower’s heavy wooden door.

Five figurines trotted out, dark steeds with fiery manes. Their jockeys wore fireproof leather. Aria whispered to Homer: “I wonder how many favors she had to cash in to get those Night Mares. They’re a pain to snatch from the wild wastes.” The gnomes placed orange spikes behind the horses to represent the fire they left in their path. “Good move, though. Seafolk hate fire. It’s alien to them.”

Jennifer crossed her arms. “My Night Mares crisscross the beach. Now I control the table.”

Sir Hitode sucked his translator’s feet. “The crabs continue to advance.” The crabs encroached on the tower, pincers snapping.

“The crabs are now close together,” said Jennifer. “My Night Mares circle them at a safe distance, like this.” She waved her finger around the crabs. The jockeys made their mounts trap the crabs in a ring of fire which threatened to fry them in their shells. “Now we finish crisscrossing the beach.” The Night Mares drew long lines of fire across the sand. “My longbowmen fire on the crabs, aiming for eyes and joints.”

Bowstrings loosed arrows. Hitode gripped his translator’s hips. “The crabs flee into the fire.” Gnomes pushed the crabs into the flames. Crab legs spasmed as they cooked.

Jennifer squinted at the burning crabs, blackened and scorched. “Cease fire,” she said, as if to her men.

Neither commander gave orders for two minutes. Jennifer’s jockeys made their mounts set the whole beach ablaze. The audience murmured, except the elves who communicated with pheromones.

The sea star switched which arm he used to wrap his gnome’s legs. “Sir Hitode would like to advance the table ten hours.”

“Fine,” said Jennifer. “My Night Mares keep the fires burning.”

Gnomes linked hands in a circle to corroborate. Then they stepped onto the table to demonstrate the passage of time at high speed. The crab carcasses crisped and fell into the inferno. The model ocean elevated as the tide came in. Two tracts of water rushed up the beach. “The crabs carved trenches. These trenches now flood.”

The crabs’ paths made a horseshoe lagoon. Jennifer’s Night Mares were stranded on a semicircular island.

“Sir Hitode advises his challenger not to indulge in pride,” said the sea star’s gnome. “He knew you would use Night Mares when you arrived riding one. Seafolk advance through the newly made channels.”

The silhouettes of seafolk squads swam toward the tower. When they met in the horseshoe’s center, Jennifer raised a hand. “I figured you’d spy on me, and I knew you’d alter the terrain to trap my troops. So I came prepared. Release the barrels!” Her longbowmen rolled barrels off the top of the tower. The barrels spilled gallons of flaming oil over the water.

The sea star pulsed. “Seafolk lift their net!” From the oil, two long metal poles protruded. The poles held a net between them. “Seafolk retreat to the ocean.” The poles fled along both sides of the horseshoe. The net caught jockeys and flung them into the fire. Horses fell to the ground, snapping femurs.

“No!” Jennifer pointed to her remaining riders. “My jockeys try to vault the trenches.”

“Risky move,” whispered Aria. “Night Mares don’t do well in water.”

Only one steed managed to make the leap, landing safely on the sand.

Others crashed against the opposite bank and fell into the water. These Night Mares flailed, howled, and melted, making the water boil, killing their jockeys. The poles sped seaward, dragging Jennifer’s straggling horsemen through fire into the ocean.

“The game is over,” announced a gnome. “The human has two longbowmen and one Night Mare with jockey surviving. Sir Hitode lost two giant crabs.” The gnomes held each others hands in a circle to calculate results. “Both commanders dealt damage, but neither can claim victory. To each side, three points.”

The crowd applauded. Emperor Shobai’s maw released bubbly chuckles.

“The next match commences shortly.”

“Not bad, kid,” said Aria to Jennifer as she sat with her and Jameson. Homer and Quattuor exchanged brass cards while more gnomes prepared the table. “Where’d you get so many Night Mare jockeys?”

“I know them personally,” she answered. “They’ll be sad to hear they’re dead, but I’ve got plenty more where they came from.”

“That’s the spirit, kid.” The seafolk’s side of the table was a clear ocean, but the beach gave way to rolling grassy hills on Homer’s side. “Homer’s fighting Ebi Anago. Do you know him? I can’t keep track of seafolk.”

“He’s Emperor Shobai’s nephew, next in line for the throne.” A new glass tank ascended into view. Within lay a lobster at least two hundred pounds with antennae two feet long. Its tail split into eight slender limbs like electric eels. “They say each of its tails has its own brain,” whispered Jennifer.

The dwarfs behind them grunted. “Nine brains?”

“Nine brains.”

Jennifer turned to see the dwarfs, but quickly turned away. “I didn’t think dwarfs were allowed in civilized lands.”

“The dock’s neutral.” One dwarf spat mud. “We’re here to watch.”

“Minotaur’s broken,” said the other. It pointed to Homer and drew his scars. Aria wondered how they knew that without eyes. “Shameful.”

“Appalling.”

“Degenerate.”

Aria folded her arms. “You’d better watch him close, because that minotaur’s gonna win the tournament and beat your champion back into the ground.”

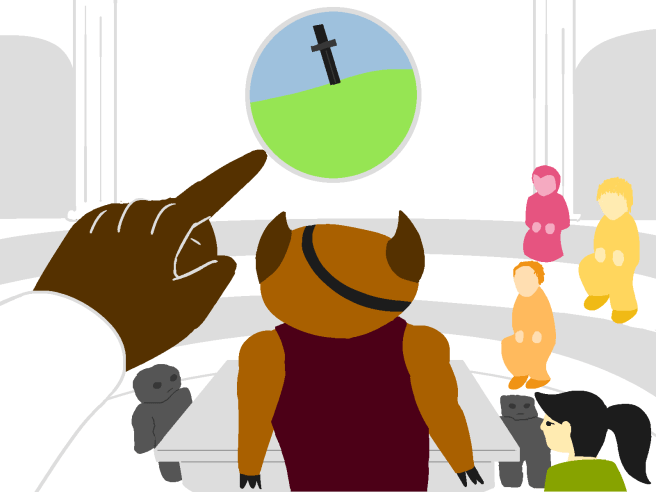

“With a red dragon?” The dwarf pointed to the table. Homer had painted Scales’ figurine bright red. Flames seemed to leap from its spiked tail and horns. On either side of the dragon, three archers prepared their bows.

“I thought Scales was a—” Jameson grunted when Aria elbowed him in the ribs.

“Red dragons are perfect against seafolk,” she said to the dwarfs. “When they’re out of the water, they’re terrified of fire. Look, Ebi Anago is having second thoughts!”

The massive lobster dangled an eel-like limb over the tank wall to to the translator-gnome’s shoulder. “The esteemed Ebi Anago says seafolk intelligence was unaware of a red dragon in human lands and would like verification on this game piece.” More gnomes clattered their fingers together and rechecked the dragon’s brass card. They confirmed the brass was genuine. “Ebi Anago would like to alter his army. Would the challenger allow this if he, too, is given the opportunity?”

Homer folded his arms. He must have picked it up from Aria. “Ess.” Without looking from the lobster, he placed a minotaur’s figurine on the table.

Jameson leaned towards Aria. “Is he playing his own figurine?” She nodded. “He could die!” She nodded again and bit her lip.

“Ebi Anago would like to congratulate his opponent before the match,” said the translator. Three gnomes arranged figurines under the model ocean. “He says he remembers centuries ago, when Emperor Shobai had to demand seafolk-inclusion in the treaty signed by humans, elves, and dwarfs to limit bloodshed to table-war. He acknowledges you as a fellow intelligent creature.” The lobster’s beady eyes locked with Homer’s dark goggles. Ebi Anago snapped his claws. “Ebi Anago says the minotaur may choose to take the first move or second.”

Homer pointed to his dragon figurine and tapped a message to a gnome. Clever gnomish handiwork made the red dragon fly, supported by almost invisible scaffolding.

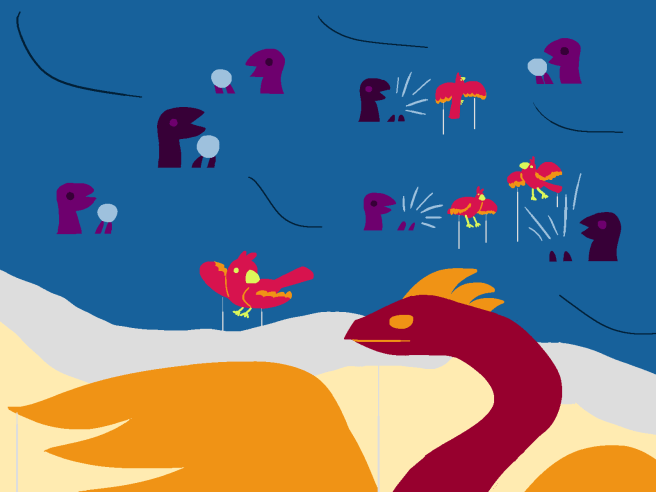

Ebi Anago’s eight tentacles flopped over the tank wall. Each tapped a message onto a different gnome’s shoulder. Aria recalled Jennifer’s warning: each of the tentacle’s brains had something to contribute to the tactical discussion. The gnomes showed how thirty seafolk soldiers like eels surfaced on the ocean. Each eel figurine held a glass ball like a bubble.

The bubbles popped; there was a bird-figurine in each one. The flock flew six feet above the table with the eagerness Aria expected from birds kept in bubbles underwater. Ebi Anago spoke through his gnome: “Ebi Anago says that having owned dragons himself, he knows they are easily distracted by movement and color. These parrots will control your dragon.” Parrot-figurines spread around the air above the table, and the dragon’s neck twisted and turned to follow them. The crowd murmured.

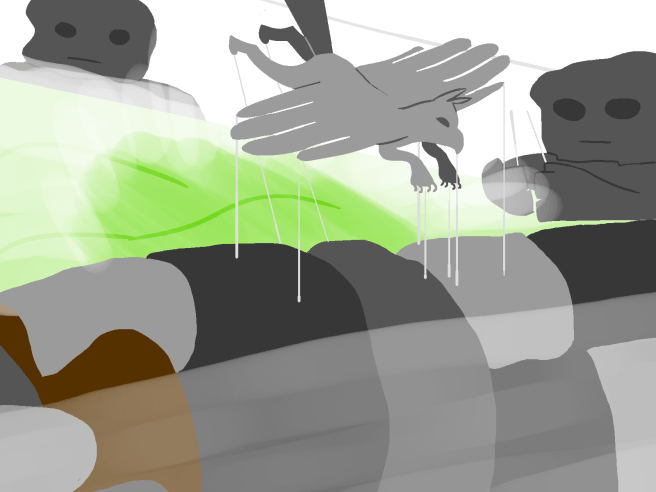

Homer tapped the figurines of his archers. Said the gnomes, “these skilled archers are able to strike down over half of the distracting parrots.” They carried away dead figurines.

Ebi Anago contacted his translator. “These parrots were stuffed with glitterbombs.” Gnomes procured, from under the table, perfume bottles filled with glitter. A few puffs showed how the shot birds exploded into shiny clouds. The elves in the audience oohed and aahed. “The dragon is incapacitated in wonder.”

Homer raised one hand to pause the table. He pointed to one of his archers in particular. A gnome checked its brass card. “Instead of arrows, this archer has an elvish cricket in his quiver. He holds the cricket in the air.” The smell of the cricket made Scales’ turn its head. “The dragon returns to Homer’s side of the field.”

While the gnomes showed how the dragon demurely begged for its food, Homer pointed to his dark goggles and tapped a message on a gnome’s shoulder. That gnome nodded and made Homer’s figurine approach the dragon. The gnomes carefully removed Homer’s figurine’s goggles and put them on Scales.

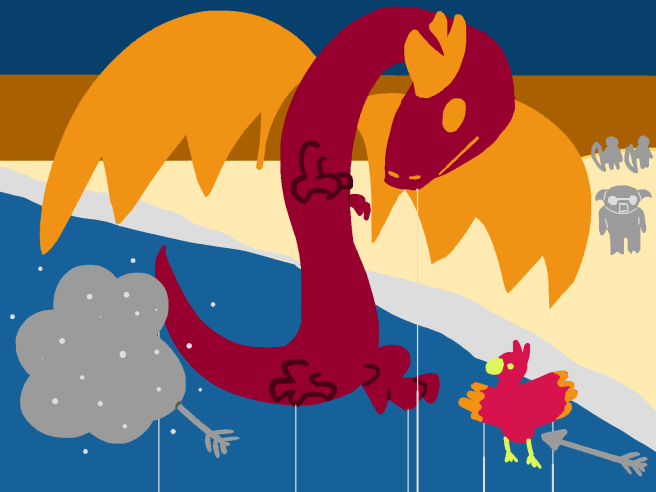

Homer pointed to Ebi Anago’s side of the table. This time the dragon flew through the clouds and parrots undistracted. It breathed deep and opened its jaws for a mighty exhale.

“The seafolk dive underwater before the dragon breathes fire,” said Ebi Anago’s translator. “As the ocean boils, they will take only minor injuries and fire projectiles from the seafloor.”

“The dragon unleashes his freezing breath,” said the gnomes. They replaced the model ocean with ice. “All the seafolk instantly freeze to death. Homer has won the match with no casualties. Five points to the minotaur, no points to the seafolk.”

Homer took his dragon’s figurine and rubbed it on his fur. The red paint smeared away. Scales, the ice-dragon, shined in the moonlight to impressed cheers of disbelief from the audience.

“Homer! His name is Homer!” Aria’s cheers rose above the rest. “I trained him!”

Homer luxuriated in the audience’s approval. He filled with a kind of warmth he’d never felt before. A gnome tugged his elbow. “A gift from Prince Ebi Anago.” It was a paper envelope.

On the return trip to human lands, they stopped for the night among quiet hills. Homer removed his goggles in the dark. Even without them, he had difficulty seeing the stars. Labyrinths demanded nearsightedness. To Homer, everything more than thirty feet away was a blur.

The unmistakable weight of a brass card gave the paper envelope some heft. The envelope was sealed with wax impressed with the image of Emperor Shobai.

He broke the seal; indeed, the envelope contained only a brass card. He tried reading the gnomish dots himself. He could tell the brass card was a small animal. It could fly. It was bright red. It was well-trained. This was one of Ebi Anago’s parrots. But there was information on the card which Homer couldn’t parse with his fingertips. Recalling the match, he realized some of the card’s dots represented the glitterbomb the parrot was stuffed with, but there was something else, too. The parrot was fed some kind of plant.

Homer turned to carriages. While Aria, Jameson, and their driver slept in the carriages, Quattuor stood completely still staring at the moon. “Guadduor.” Homer tapped his shoulder.

The gnome’s fingertips twitched as if sleep-talking. “Homer,” it said. “I am conserving energy. What do you need?” Homer gave him the parrot’s card. “This is one of Ebi Anago’s parrots.”

“Bland.”

“Bland?”

Homer pursed his lips unnaturally . “Pland.”

“Plant! Yes, the parrot has eaten a plant called lillyweed. It grows in swamps between elven and dwarven territories.” Quattuor returned the card. “How interesting. Lillyweed is toxic to ice-dragons, but not red-dragons. Ebi Anago must have known the whole time.”

Homer furrowed his thick brow at the back of the card. Gnomish dots were engraved: “When you revealed your painted dragon, I thought I’d won. Your dragon couldn’t freeze my parrots without revealing your deception; you’d have to shoot them with arrows or let your dragon eat them, and both, I believed, would win me the game. But the better player won.

“If you ever need help from seafolk, give this card to a gnome and have them take it to the core to contact me.

“Ebi Anago.”