(This is part nine of a fantasy series starting here. Today Homer the minotaur must defeat a dwarven computer at table-war to protect the planet from actual bloodshed.)

Over centuries, the dwarfs had eaten their corner of the continent to a flat, lava-pocked landscape. At night the glowing magma-pools spat back at the cold, dark sky. Homer warmed himself by a red-hot pit. Radiating heat made his goggles sear him, so he took them off.

The human embassy was walled off with stalagmites gnawed into shape by the dwarfs. Dwarfs hid behind the spikes to watch Homer through their eyeless helmets. Homer checked his pockets. He had a brass card he’d received as a gift from Ebi Anago, nephew of the emperor of the seafolk.

Homer dropped the brass card in the magma pit. Immediately a gnome crawled from the liquid rock. This gnome’s fresh body was marble-white and crackled as it cooled. “Greetings. I represent seafolk trading services. How may I help you this fine evening?”

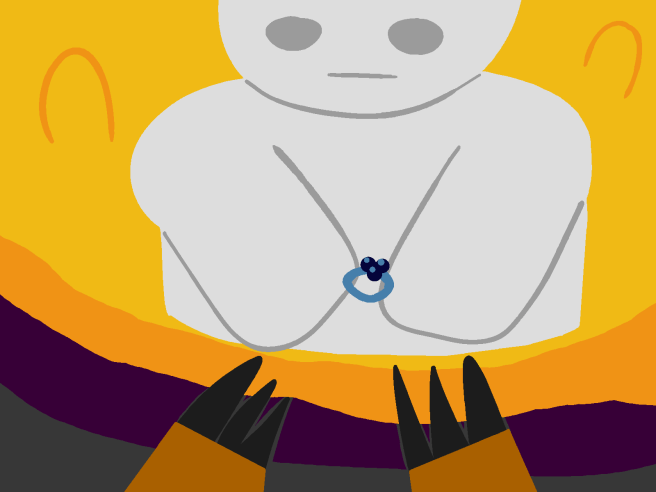

“Uedding.” Homer mimicked donning a necklace. “How much?”

“You want to buy a seafolk wedding necklace?” The gnome cocked his head. “Who is it for?”

“Gween.”

“A royal wedding necklace would cost a fortune,” said the gnome. “Forgive me for doubting you have the funds on hand.”

“Ebi Anago.” Homer snapped his palms like lobster claws. “Frend.”

“You know Sir Ebi Anago? Excuse me.” The gnome sank into the magma. After a few minutes, a magma bubble popped and the gnome emerged once more. “The esteemed Ebi Anago is grateful to hear from you, and sent me with this token of appreciation. He says this is more appropriate than a necklace for a surface-dweller’s wedding.”

The gnome pulled open his own torso like a chest of drawers. Inside sat a ring fit for a human’s finger, with a band of not gold, nor silver, but some shining blue element. Atop were three dark sapphires.

“Ebi Anago hopes this demonstrates the eternal gratitude owed you by all sentient beings for your assistance securing sovereignty for the wild wastes. But if it does not please you, he would gladly replace it and fall upon a sword in shame.”

Homer took the ring.

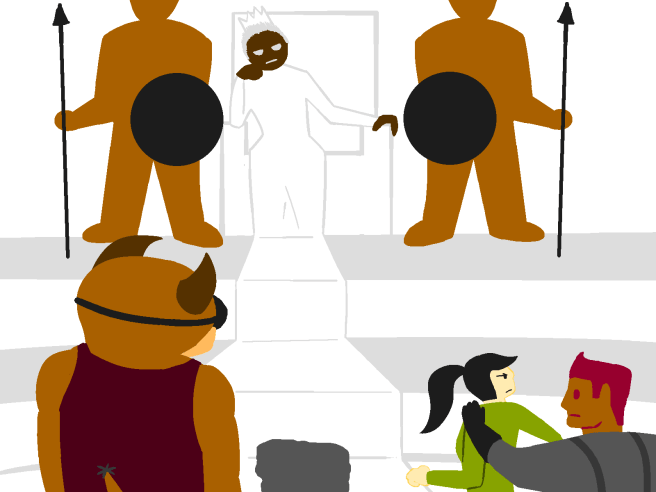

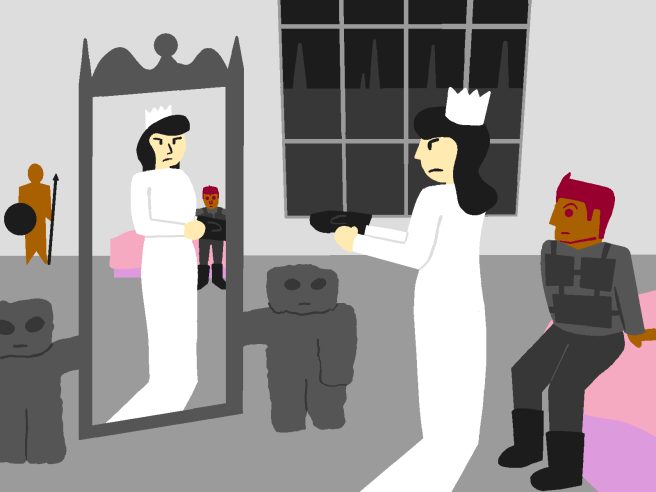

In the human embassy, Aria shook wrinkles from her new white dress. The black glove she wore over her burnt right hand barely fit through the delicate sleeve. Gnomes held a tall mirror for her. Despite the attempts of ten tailors, her arms and legs were still too long for the dress. She felt like an elven brood-mother, twenty feet tall and spindly thin. “I don’t like it at all,” she told her gnomes and royal guards. “Anthrapas wore a dress, but that’s not me. Would a military uniform be queenly enough?”

“I suppose it’s up to you,” said Sir Jameson, “but Anthrapas never dressed like that.”

“I’m queen. I’ll wear what I want.” Aria smeared off her make-up with her black glove. “Everyone out. I’m changing again.”

Aria appreciated her bedroom more when it was empty. The human embassy in dwarven land was adorned with luxurious crystal chandeliers, but smelled like rotten dwarfs.

Aria sighed and looked back into the mirror. “Maybe I could wear this just during Homer’s battle, to prove I’m queenly.” She tried to walk; her heels speared her dress’ hem and tore it. “Uugh. No.” She kicked off her shoes and stepped into her boots. “They’ll have to take me as I am.”

Someone knocked at the door.

“Come in.”

Homer stooped to slip his horns through the slim doorway. “Arra?”

“Hey, Homer.” Aria stuffed all her make-up into a drawer. “I’m glad to see you. Ever since I became queen, I’ve had to talk with just royal guards and gnomes. And—eugh—dwarfs, and elves. How are you? Are you ready for your match? The first to ten points decides the fate of the planet.”

Homer looked her up and down. “Dress.”

“I hate it,” said Aria, “and not just the dress, I hate all of it. It’s just like Anthrapas to leave me all the heavy lifting.” She tied her hair in a ponytail. “She knew me too well. I’ve gotta be a great queen, not because I care, but because failure would humiliate me. I’m too prideful not to give it my all.”

“Nod alone.” Homer lifted his goggles and presented the wedding ring.

Aria Twine caught her knees before they buckled. “N-no.”

Homer didn’t recognize the disbelief on Aria’s face. Maybe she just didn’t understand. “I lov—”

“Don’t say it.” She struggled for balance. “Oh god, this is wrong.”

“Arra?”

“No, no, no… I’m so sorry.” She couldn’t keep her hands from trembling. She turned away. “I’m a human and you’re a—it’s just not right, Homer. You can’t love me like that. I was—” She shook her head. “I’m taking advantage of you, Homer. Like a beast of burden.”

Homer pointed to her black glove. “Burned your hand.”

“I burned my hand for me, not for you.” She cried onto her white dress. “Homer, you’re an intelligent, emotional animal. Don’t you deserve to love someone who isn’t just using you? I can’t do this. I just can’t.”

Homer looked at the ring. He left it on Aria’s dresser. “Gift, then.”

“Homer!” Aria chased him to the door, but Homer was already gone.

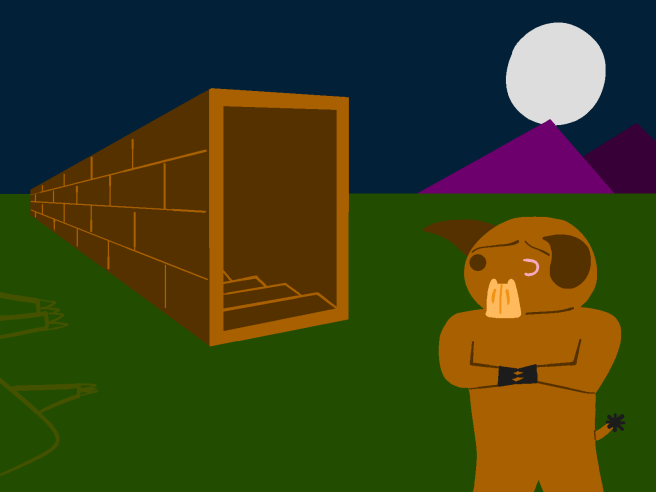

Homer wasn’t sure where he was running—just away from the embassy, away from the dwarfs, and away from any life he remembered. His breaths became fog banks in the night, clouding his vision and his mind. He tore off his vest and pants and goggles. His hooves hit the hard earth, and his back hunched forward until he bounded over the ground like a wild animal on all fours. Propelled by the vacuum left in the pit of his stomach, he finally left the jagged dwarven mountains behind and entered the wild wastes.

The full moon cast his shadow across the shifting terrain: icy plains, then baked deserts, then grassy hills, then gaping craters. He navigated not by starlight or compass, but by red madness at the corner of his eye. Even without knowing what he searched for, he knew when he found it.

A rectangular hallway protruded from the earth. Hewn of solid stone, the hall led into the darkness of an underground labyrinth.

The door was large enough for Homer to enter at full height without hitting his horns. His hooves recognized the cobblestone floor. A fork in the hall ahead split into two paths both leading deeper into the dark.

Scents made Homer recall buried images. Curving corridors. Sloping stairwells. Facades, forks, branches, and ladders. For every month Homer had lived on the surface, he’d previously wandered a year in the maze. It called to him.

What had the surface ever done for him? He felt the scars on his chest. At least the maze would host more minotaurs for company. Whenever Homer had met another minotaur, they had kindly shared their food and their maps of the maze.

He smelled minotaurs even now. Where? He sniffed left and right at the fork, but the scent was strongest behind him, at the maze’s exit. Homer jogged back to the surface; maybe his new minotaur friends had escaped the maze just recently.

There they were, lying in the grass. He’d missed them in the dark: a male, a female, and a child.

Their heads were missing. Their bodies were warm.

They reeked of dwarfs.

“Homer?” Three gnomes lounged by the dwarven magma pits, just far enough away that their dresses didn’t catch fire. “What are you carrying?”

Homer slung the three minotaurs onto the ground. “Dwrfs.”

“Oh dear.” The gnomes inspected them. “You think dwarfs killed them? We are supremely sorry. There is no law against killing animals in the wild wastes, not until the sovereignty of the wastes is ratified.” Homer pointed to the boiling pit behind them. “You wish to burn them?” Homer nodded, shoulders quivering. “Homer…” Two gnomes held Homer’s hands. “Only gnomes are rejuvenated by magma.”

Homer nodded. He knew that already. He dropped the three bodies in the pit. Fire spread across their dried fur like burning grass. The bodies slowly sunk.

“There was a time gnomes knew sorrow. The whole collective gnomish consciousness could cry and cramp in anguish.” The gnomes removed their dresses to join Homer by the pit without combusting. “I say this not to diminish your pain, but to say that although centuries have passed since that time, we understand. If I were still capable of emotion, I would feel such agonizing empathy for you that dormant demons might split open the earth to rip me limb from limb to end my suffering.”

For a minute the only sound was bubbling magma.

“Make no mistake, Homer, emotions are perhaps the most powerful force in the universe. These scars will shape you, but, they do not constitute you. You are more.”

A gnome gave Homer his goggles. Homer put them on.

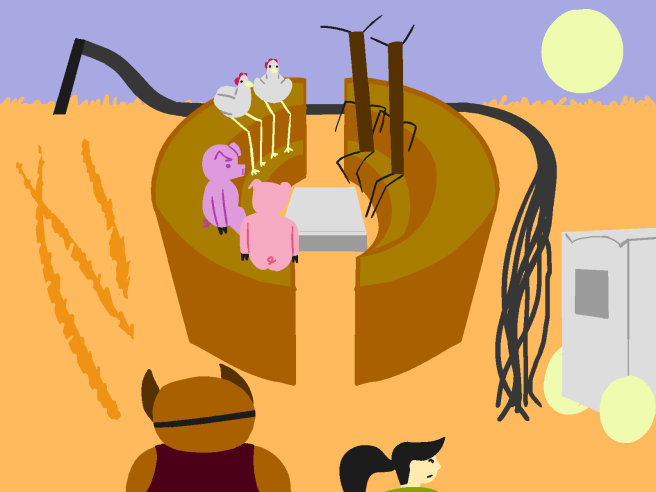

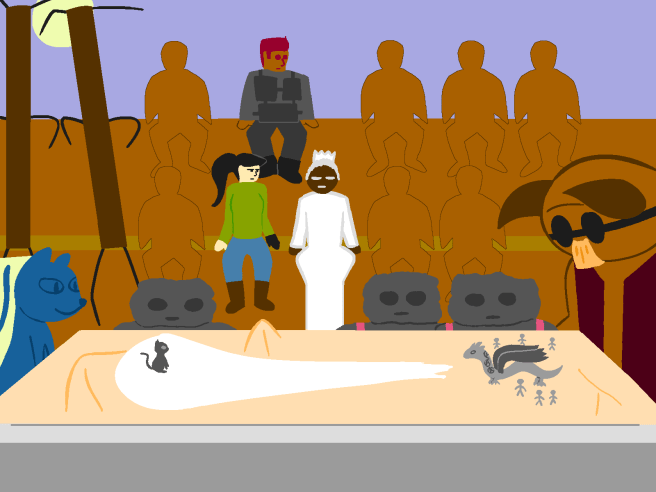

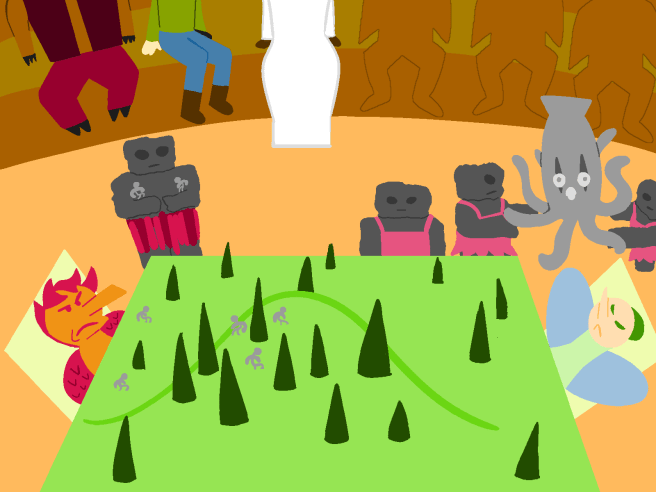

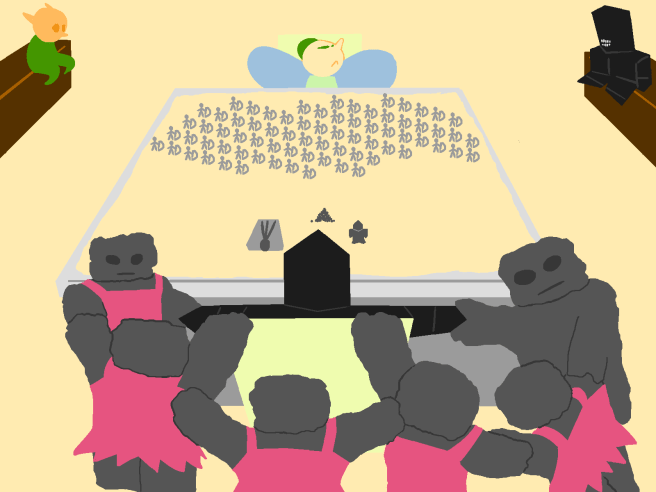

The Mountain Swallower’s throne room was ten times larger than the whole human capital, and had enough seats for armies. Dwarfs filled the northern half the room around the Mountain Swallower’s vacant throne. Their eyeless helmets watched the other races enter. The elves fluttered in with the humans, and then gnomes wheeled in the seafolk trapped in their glass tanks.

Emperor Shobai wiped morning dew from his tank with a long crab leg. His wife floated beside him. At Shobai’s direction, the gnomes wheeled them to the eastern side of the room beside Ebi Anago and Sir Hitode, the lobster and starfish commanders. The centaur, sphinx, and harpy took seats beside the seafolk, each bowing to the other races in whatever manner they were able.

On the western side of the room, Madam Commander Victoria took the center chair to represent the elven queen many miles away. Stephanie sat beside her, pouting.

Humans sat on the south side. Harvey and Jennifer waited for their queen.

The Mountain Swallower’s footsteps echoed and shook the room. Their voice shattered the air. “Shobai.”

The seafolk emperor released bubbles from his maw.

“Victoria. Standing in for your queen?”

Victoria nodded.

“Beasts.”

The centaur, sphinx, and harpy nodded.

“The human queen is absent,” said the Mountain Swallower. “A pity she won’t witness the end of the world.”

The room stirred. Emperor Shobai tapped his gnome on the shoulder. “The emperor is concerned about your intentions today,” said the gnome. “Could you clarify your aim?”

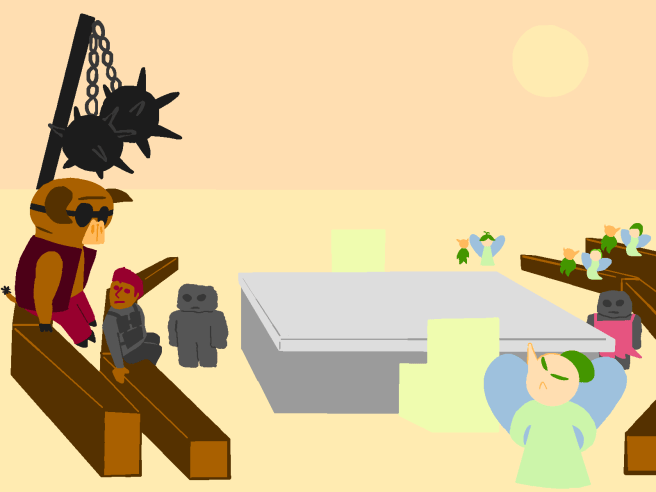

The Mountain Swallower didn’t move. “When we defeat the minotaur, we will be freed from the treaty limiting us to table-war. We will wipe out all other life and restore our kingdom to its former glory. Before you protest, recall that dwarfs have never violated the law. Our means justify the end.” The Mountain Swallower barked at the door. “Enter, minotaur.”

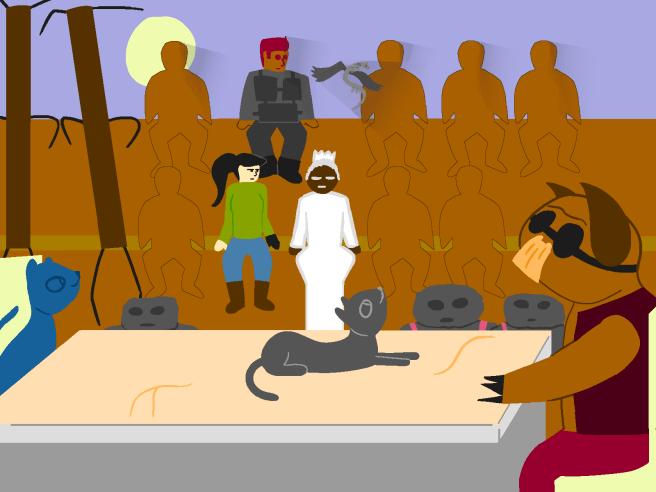

Homer’s goggles and strong jaw seemed like a stone statue’s, as if he were carved from a mountain. He sat at the war-table with a bag of brass cards and figurines.

The Mountain Swallower leaned forward in their throne. “How sad that the dwarven race’s final challenge is scarred and disfigured.”

Homer considered words carefully, and eventually decided his mouth wasn’t adequate. He put his hand on a gnome’s shoulder. “I’m not your final challenge,” translated the gnome from Homer’s finger-taps.

“Mm?”

“And you’re not my final challenge, either,” translated the gnome. Homer organized brass cards on the table. “You’re just another fork in my path.”

The Mountain Swallower laughed. It was ear-splitting, like a violin played with a steel wool bow. “Such arrogance,” it whispered. “Bring the machine.” The room flooded with shadow. Gnomes had covered the windows—these gnomes had limbs gnawed off by dwarfs.

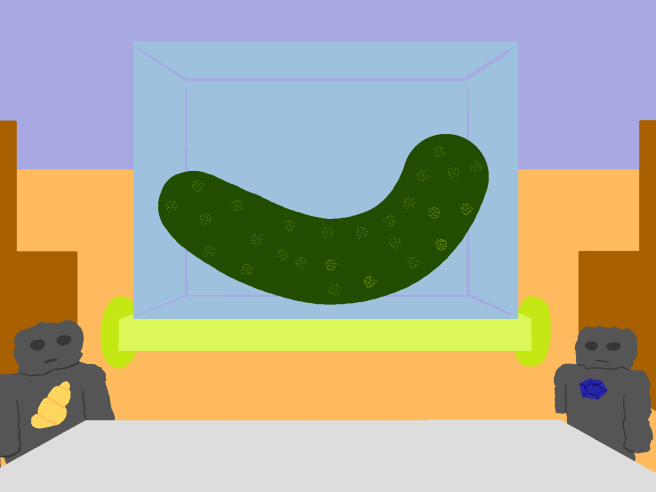

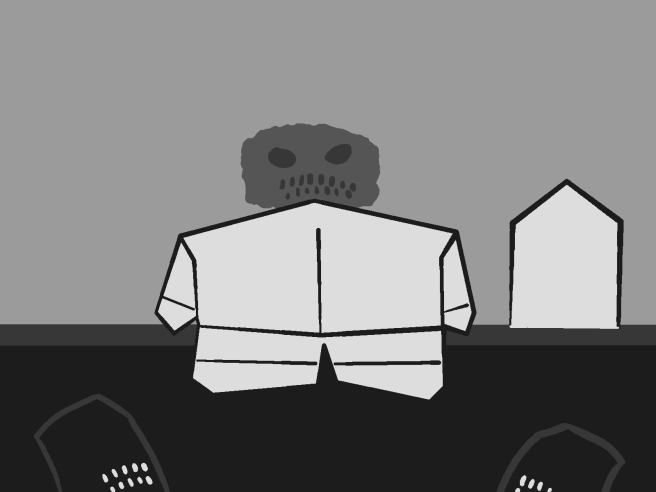

The machine was no longer merely a silent dwarf. It was a box five feet wide, five feet thick, and ten feet tall, covered in dwarven relief. The box wore a skirt of gnome arms, palm out, fingers spread, ready for input and output.

Its front face was decorated with minotaur skulls.

“Inspired by your success, we briefly experimented with minotaur brains. We’ve concluded your heads are best as ornaments.” The Mountain Swallower beckoned their gnomes to deposit the machine opposite Homer at the war-table. “This box has one thousand gnome brains wired together. It is unbeatable.”

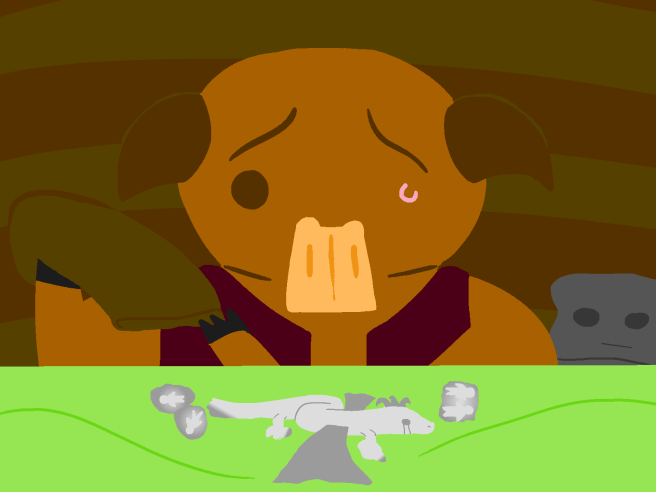

Homer grieved over the minotaur skulls. Their horns curved up like the trunks of broken trees. The bony smiles reflected in his dark goggles.

“The first to ten points will decide the fate of the planet, minotaur,” said the Mountain Swallower. “Let us—”

Homer interrupted through his gnomish translator. “When I win five points in the first round, I want your helmet.”

The Mountain Swallower chuckled. “Ha! And when my machine wins five points in the first round, I claim your goggles. Begin the match!”

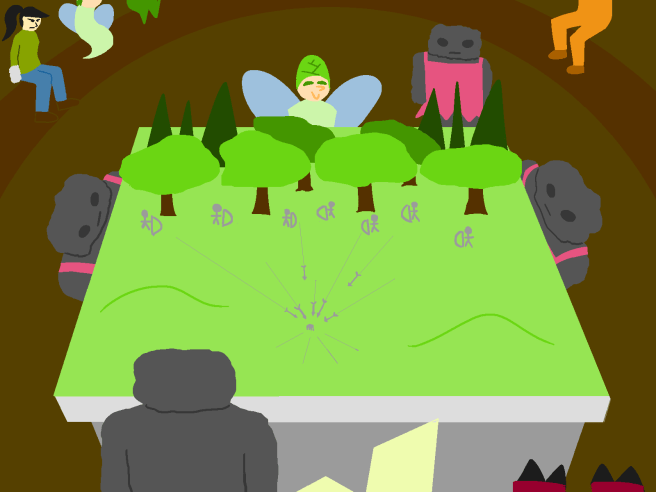

Twenty gnomes poured from the stands. Some were bare, others in elven dresses, others decorated with jewels. The dwarfs’ gnomes stumbled out half-blind, feeling with hobbled arms and legs. One gnome stood on the table. “The minotaur may choose the location of the first battle. Oh…” Homer gave the gnome a brass card. “The battlefield is chosen.”

“Gnomes!” shouted the Mountain Swallower. “Tell our machine where the war will be!” Gnomes surrounded the machine and matched the disembodied hands around the circumference. The gnomes conveyed the location to the machine, and the machine buzzed and hummed. A brass card popped out a slot detailing the army the machine would bring to battle. A gnome pulled open a drawer on the machine and retrieved two figurines: a dwarf and its ballista. The gnome aimed the ballista exactly as the machine dictated.

Homer took a figurine from his bag: Scales, the icy dragon. Scales had hatched only a year ago, but Aria’s prescribed diet of elven insects had built him into a massive beast who breathed blizzards.

The gnomes swiftly built the table’s terrain. Black spires and sandy wastes were signatures of dwarven territory.

“Over before it even begins,” said the Mountain Swallower.

Homer nodded in agreement and put his dragon on the table.

“The game starts,” said a gnome.

“Ennd.” Homer extended a hand. “Hellmet.”

The crowd murmured, perplexed. A gnome met Homer to inquire digitally. “He says inspecting the battlefield’s physical location will prove he has already won.”

The Mountain Swallower barked. Ten dwarfs picked up a gnome each and hustled from the throne-room. “Don’t waste my time, minotaur.”

As minutes passed, humans and elves chatted and pointed at the machine. The seafolk traded their gnomes from tank to tank carrying conversation between them.

“Homer, are you okay?” Jennifer pat his shoulder.

“We’re all here for you,” said Harvey.

Homer shook his head. “Arra?”

Jennifer sighed. “We don’t know where she is. She’s probably busy with queenly duties, but I can’t imagine anything more important than this.”

“Mmm.”

The dwarfs reentered and tossed their gnomes onto the table. “Upon closer investigation,” said a gnome, “there is a deep hole in this exact spot, underneath your units.” He dug with his hands. “It was disguised with thin branches and leaves smoothed over with brown dust. The hole is lined with sharp, pointed sticks.” He dropped the dwarf and ballista into the pit. “Five points to Homer.”

Seafolk bubbled in their tanks. Humans and elves cheered.

The Mountain Swallower’s teeth barely parted. “Cheat!”

Homer shook his head and matched hands with a gnome. “Homer says he dug the hole himself last night.” Homer took Scales’ figurine. “Would you protest the death of your armies if you commanded them to swim into the sea? You lost because of our adherence to physical accuracy.”

The Mountain Swallower rapped the stone throne. “…Very well,” it said. “You win the first round.”

Homer extended his hand. “Hellmet.”

The lord of the dwarfs paused, teeth together, then pulled off its helmet.

Under the helmet was the lipless and misshapen, but unmistakable, face of a gnome. The Mountain Swallower tossed their helmet onto the war-table. The audience was silent. The Mountain Swallower explained for the stunned mortals:

“There was a time gnomes and dwarfs were the same. When the earth was born, we were born with it.” All the gnomes in the room nodded in agreement. “We ate rocks. We craved gems. He enjoyed the heartbeat of hell. The earth was ours and all was right.”

Homer took the helmet and looked into its face-plate.

“But soon, we had siblings. The seafolk were first, cretinous, chitinous creatures scuttling in the depths. Then the land bore humans, elves, and animals. We despised all these lifeforms for daring to invade our existence. We thought we would never be rid of you parasites. But then, a thousand years ago,” said the Mountain Swallower, removing a gauntlet, “between the inner mantle and the core, where heat and pressure blurs the line between reality and the immaterial, we found them.”

The Mountain Swallower raised their bare forearm. It was scarred as if by a branding iron in the shape of a twisted screaming face.

“Nameless demons from beyond the pale. This is the demon with the great black axe.” They removed another gauntlet to show another scar. “Who wielded the great black sword.” Under the chest piece were many more intricate wounds. “Whose great black whip cracked the continent. Who bore the great black spear. The twin-headed monster with great black twin-headed flail. And their leader with a great black trident.”

Homer squinted at the dwarf’s chest. Symbols from hell burned their rocky skin to charcoal. The scars circled like chains or snaking serpents.

“The demons were trapped in that hot, dark place by unknown entities from bygone eons. Their fiendish intelligence soon convinced us: if we freed them, the earth would be ours again. We made deals with each one, and with each deal the demons grew, until they blotted out the sky.

“True to their word, the demons wreaked havoc on the surface. Humans, elves, and seafolk all struggled to kill them, then to subdue them, then to flee from them, and then, finally, to merely survive them.

“But soon we realized our mistake. The demons’ footsteps, and their malicious laughter, shook the planet to its core. We were hurting our own mother. The demons had to be stopped. But we had already given ourselves to them, and were therefore powerless against them.

“But the planet reacted as if consciously. The core cracked, and we were split into gnomes and dwarfs. Only dwarfs were saddled with the pacts they’d made, and gnomes escaped those promises by ejecting the natural greatness of our race.”

The Mountain Swallower leaned forward.

“A thousand years ago, we were Eden’s members. The sensation of being primordial, and being connected by magma to all sentient beings—I lost that. And gnomes, poor gnomes, are the only creatures who can globally commune through magma, and regenerate their injuries, but they don’t enjoy it. Dwarfs aren’t afforded those luxuries, even being more deserving for the crosses we bear.

“But the demons were powerless before the gnomes, who were unburdened by desire. When the gnomes were finished renegotiating our pacts, the demons were barely bigger than beads. The gnomes also organized a treaty limiting the surface-world to table-war. For our own safety, we dwarfs conceded to that treaty. Until today.” The Mountain Swallower stood tall and folded its arms. “Today our machine defeats table-war and binds those demons to our whim once more. Today the earth reclaims its chosen race.”

Homer bit the helmet. His flat, bovine teeth worked the metal until it tore. He threw the helmet on the ground and stepped on it. “Negst round.”

The Mountain Swallower beckoned three dwarfs to remove a panel from the machine. They rearranged gnome brains, twisted screws, and filed brass cards. “Minotaur, my machine is improved and will not lose again. Would you accept another wager?” Homer glared at the lord of the dwarfs. “If you earn even one point this round, I’ll give you all the wealth of the dwarfs. If you earn nothing, I’ll take your goggles to replace my helmet.”

Homer nodded.

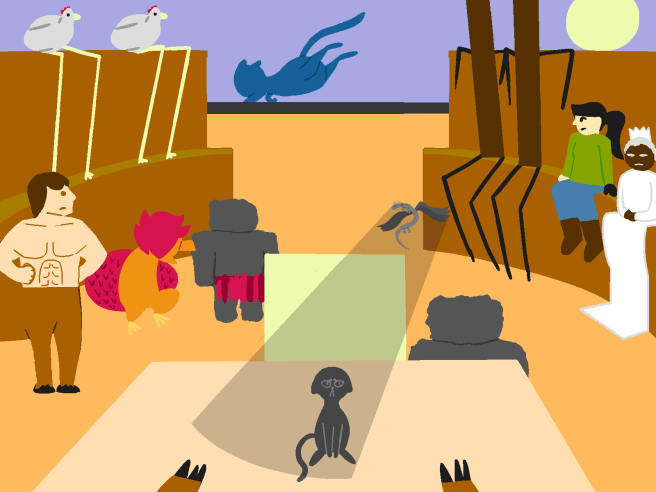

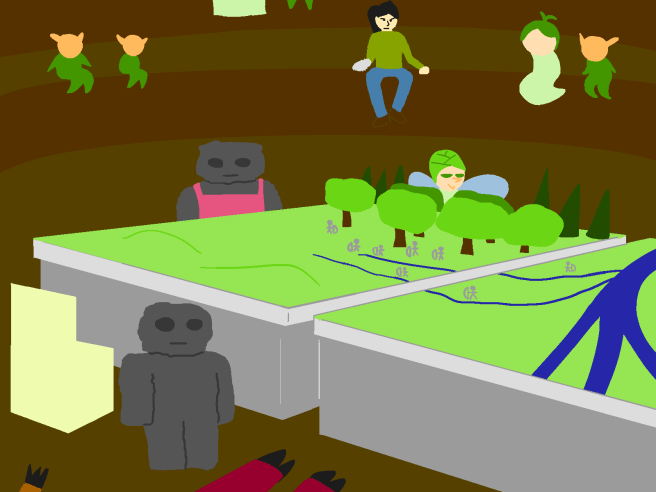

“As loser of the previous round, the dwarven machine has the choice of battlefield,” announced the gnomes. They surrounded the machine to let its skirt of hands tell them where the next battle should be. The map they built on the table had sinister, burnt-black trees jutting from the ground.

While he waited for gnomes to finish the map, Homer wondered if the machine was watching him. Was it blind like a dwarf? Maybe the gnomes informed its skirt of hands of Homer’s every movement.

Homer snapped from wonder when the gnomes put a figurine on the table: a giant squid, like the one Madam Victoria had used in the battle against the harpy. The harpy gasped, and Homer realized it was in fact that same squid: in official table-war canon, the squid’s corpse had rested here since that battle. “What happened to my homeland?” squawked the harpy. “It looks like a cemetery, bukawk!”

“It is a cemetery,” said the Mountain Swallower. “Your battle was a bloodbath.”

If the gnomes put any figurines on the table at the machine’s behest, Homer didn’t notice them doing so. This made him anxious. Homer won his first-ever table-war using undead skeletons, so he reasoned the squid might be his main antagonist. He put six men on horseback onto the table.

“That match begins,” said the gnomes. “Homer has the first move.”

Homer held up four fingers and moved them in a circle. The gnomes made four of his horsemen trot circles around the squid; the horses left flames in their wake. “My Night Mares!” whispered Jennifer to Harvey. “Good choice!” The squid’s corpse was ringed by fire.

The machine was silent. For a moment Homer wondered if the machine even realized a battle was underway. Then the gnomes made the squid wriggle. The Mountain Swallower laughed. “I suspected my machine would infest the table with dwarven grave-worms. Ordinarily we consider them pests for filling cemeteries with fragile, worthless zombies, but when you won your first match with skeletons, we learned the value of the undead.”

Homer frowned. “You sah my madch?”

“Of course,” said the Mountain Swallower. “Dwarfs can’t communicate through magma, but I can still know anything any dwarf knows, and I relay my knowledge to my machine. Observe.” The Mountain Swallower bit the head off the nearest dwarf and swallowed without chewing.

The squid clambered toward the ring of flame. Homer muttered. “Firr.”

“I’m sure your fire could contain my squid,” said the Mountain Swallower, “as old corpses are hardly hardy. Let us see what my machine has planned.”

As soon as the lord of the dwarfs finished speaking, gnomes extinguished the ring of fire, and even the manes of Homer’s Night Mares. “It’s raining,” said a gnome.

Homer grabbed that gnome by the shoulder and asked, with gnomish finger-taps, “Did it really just start raining in the harpy’s homeland?”

“No,” said the gnome, “but the harpy’s real homeland is not a cemetery, and cemeteries rain quite often. The machine surely predicted this, having a thousand gnome-brains. Anything we know, it knows.”

Homer gnashed his teeth.

The gnomes made the squid lumber toward the Night Mares, bind them in tentacles, and eat them and their jockeys. “Check brasses!” Homer seethed. He raised two fingers, for the two Night Mares who hadn’t run circles around the squid.

The gnomes reviewed the Night Mares’ brasses. “These two Night Mares are not carrying jockeys,” they said for the audience. “They are carrying mannequins stuffed with poison.”

The Mountain Swallower’s teeth parted. “It is toxic to squids?”

“It is,” said the gnomes, “but not squids who have already died. The squid remains reanimated. Zero points to the minotaur.”

Homer’s fur stood on end. The human audience behind him murmured at the maze of scars revealed on his back.

“This is the first time in the history of table-war that a commander has ended the battle with more troops than it began with,” said the gnomes. “So, for the first time in the history of table-war, we award nine points to the machine.”

The floor around Homer cracked.

A labyrinth erupted around him, showering the room with debris and tossing the war-table into the air.