When Aria woke, she was frigid. Her wood cabin’s interior was frosted with frozen dew. Her blankets’ edges dangled icicles. “Uuugh.” She pulled herself from bed. “Scales! Scales, get out of here!”

She quickly donned overalls, thick wool socks, and boots and finally stopped shivering. She pulled two heavy leather gloves over her hands and knelt to peer under her bed.

“Scales! I said get out!”

A chill wind blew through her hair. There was a dragon under her bed, four feet long and covered in silver scales. Its white muzzle puffed icy flakes from two slim nostrils. When it stretched, the icy armor it accumulated overnight cracked and slid to the floor. Its stubby legs made Scales look like a salamander, but no ordinary lizard had talons quite so much like jagged icebergs.

“Come on. You belong outside.” Aria reached with her heavy leather gloves, but Scales slipped from her grasp. “You’re lucky I’m in a good mood this morning, Scales.” She stood again. “Hungry?”

She returned to the bed waving a long carrot and Scales stopped slithering to watch. Aria offered the carrot, but when Scales bit its tip, she nabbed the dragon by its neck and plucked it into the air.

“Gotcha.” A smile trickled across her face as she pushed open the cabin’s door with her shoulder. “You’re getting new fodder today, Scales. Soon you’ll be too big to sneak indoors.”

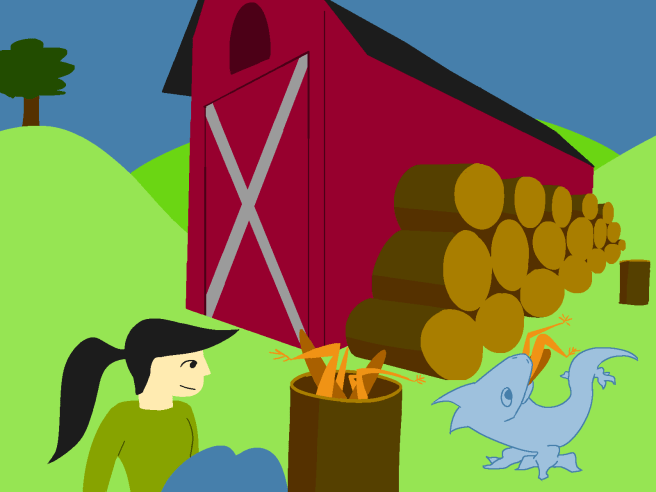

The cabin’s interior was twenty degrees colder than the summer morning air outside. The sun’s first beams rolled over grassy hills. The light was split by the shadow of a colossal black ax lodged in a forest near the horizon. The ax’s handle towered a mile tall, dividing clouds just like its head scarred the glade.

Aria released Scales. She threw the carrot and the dragon scampered after it. Its footsteps strangled grass with frost tendrils. Aria knew it wouldn’t roam too far, because it could hardly leave her alone.

“You’re early, Mr. Gnome, sir.”

The gnome stood between three and four feet tall. His rocky skin seemed to have gravel embedded in it. He wore a frilly little pink dress and dark goggles. “Good morning, Ms. Twine. I’m here on behalf of the elves buying your imps.”

“You don’t need to wear a dress just because elves tell you to. I’ve got wee overalls you could borrow.”

The gnome shrugged. “Novelties like wardrobe mean little to me. Dresses and overalls are equivalent.”

“Then change into overalls.” Aria tossed him a pair. “This is a monster farm. Dress like it.”

“Of course, Ms. Twine.” The gnome removed and folded his dress before donning the overalls. His skin was rough and gravelly all over.

“Follow me, the imps are in their enclosure. And call me Aria. What should I call you?”

“I am Septem Decim. Please show me your identification.”

“Right here.” As they walked she gave him a slim brass card about the size of her palm.

Septem felt the card with his stubby fingers. Engraved in the brass was a grid of tiny holes; the gnome’s fingertips detected their varying depths with perfect accuracy. “…This says you are deceased.”

“In the game, yeah. Ten years ago.”

“Ah, I see…”

“Hey, you speak great English for a gnome. Have you ever refereed?”

“I am a diplomat. I have only refereed unofficially in table-war hobby-shops.” Septem returned Aria’s brass.

“Oh really?” She gave him a slim wooden card. “How much would this be worth?”

Septem manually inspected the card. “This is a reproduction of your old brass for table-war hobbyists, isn’t it?”

“It’s me at my prime. Do the geeks use it often anymore? Do fans win matches in my honor?”

Septem didn’t sugarcoat it as he returned her card. “Perhaps it would have some value to historians, but I’ve never seen it used in competitive play.”

Aria sighed and tucked both cards in her overall pockets. “Let’s change the subject.”

“Another gnome was found decapitated by the dwarven border.”

“Sorry to hear it.” They approached an apple-tree covered by translucent mosquito-netting. Aria untied a rope to open the net. “Breakfast! Piknik, Togdag, Gumdrop, get your milk.”

A tinny voice like a squeaking rat called from under the apple-tree’s roots. “We saw! Don’t think we didn’t see!”

“What did you see, Togdag?” Aria pulled the cork from a jug and poured milk into a shallow saucer.

A different voice, like a chirping bird, called from the upper boughs. “You fed Scales!”

“Why was he fed before us?” called a voice in a knothole.

“Tell you what.” Aria dropped three cherries in the milk saucer. “I’ll add cream today. Will that make up for it?”

“Barely!” called Piknik.

“But you all have to line up for Mr. Decim, here,” said Aria. “Bring your brass! Chop chop!” While Aria measured cream from a smaller jug, Septem Decim watched the imps emerge from hiding. Two were red, bat-winged creatures in loincloths of weeds and bark. The third was a fairy in a dress of leaves with an apple-blossom tied in her wild green hair. They all fluttered to the ground, barely a foot tall apiece, carrying brass cards almost too large for them to hold.

The gnome scanned each brass card with his fingertips. “If it’s any consolation, to a table-war hobbyist, your imps would each be worth ten of you.”

“Thanks, I guess,” said Aria. The fairy-like Gumdrop giggled, revealing teeth longer and sharper than her pretty face suggested. “You three, come eat breakfast.” The imps swarmed her. “Ow! Gumdrop!”

“A parting gift!” giggled Gumdrop. Aria held her finger. The imp had drawn blood even through heavy leather gloves. “We’ll miss you, Twine!”

“What’re you trading us for?” asked Piknik. “You’d better not give us back to the dwarfs. You’ll never see imps like us again!”

“Ah, shoo. I’m glad to be rid of you,” she joked. “I’m trading you to the elves for dragon fodder.”

“It is not my place to speak of such things,” said Septem, “but the elven queen is procuring many powerful game-pieces. Tensions on the elvish/dwarven borders have heated. The pressure will only escalate. Ms. Twine, would you like me to brass your dragon, just in case?”

“No, not yet.” Aria cast her gaze around her farm.”Where are your elves, anyway? I thought they’d arrive with you.”

“We came across a distraction.” When the gnome left the net, the two red imps tried to sneak out with him. “Perhaps you could assist?”

Aria shoved the cork back in the milk jug. “What’s wrong?”

“You are a monster tamer, correct?”

She smiled. “Or so I’ve heard.” The gnome tilted its head, confused. “Sorry. Yes. I’m a monster tamer.”

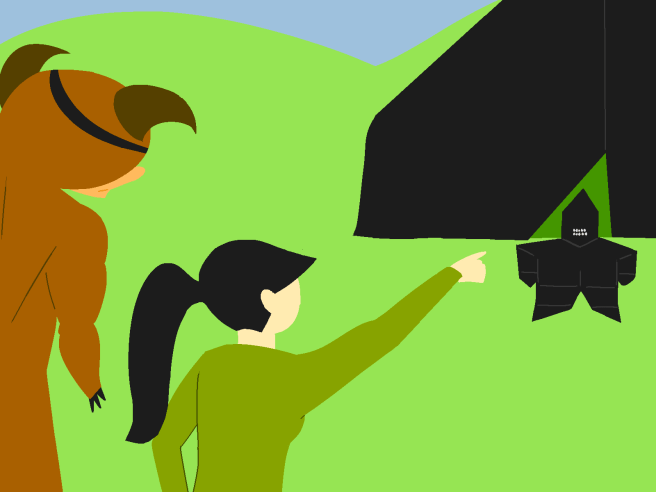

“A minotaur escaped its labyrinth near the Great Ax’s fracture. The elves sent me ahead while they captured it.”

“A minotaur?” Aria scowled and adjusted her gloves. “Let’s go.”

The Great Ax had stood there for as long as Aria could remember. Its double-bladed dwarven design was hungry for war. Its massive head was buried in the forest as if some giant had tried to cleave the earth in half, creating a clearing ten yards wide and hundreds long.

“Ugh.” Aria groaned. “The Demons’ weapons have always freaked me out.”

“You are too young.” Septem adjusted the hem of his pretty pink dress. “What is ‘freaky’ are the monsters which forged them.”

“What?” Aria adjusted the straps of her backpack. “The Demons didn’t make those weapons, the dwarfs did.”

“I stand by my statement.”

“Oh. Harsh.”

“Not harsh enough,” said Septem. “Even the dwarfs agreed to a peace treaty to escape the war they started. You can’t imagine how awful it was, for even dwarfs to regret it.”

Aria held her tongue. Dwarfs and gnomes could live long enough to remember the war against Demons centuries ago, but humans didn’t have that luxury.

When they entered the thin clearing, Aria saw a few figures near the narrow crevasse carved by the Great Ax. She squinted to count three elves, two gnomes in dresses, and one big brown minotaur. “Septem, hurry!” Septem’s tiny legs carried him as quickly as they could while Aria sprinted ahead rummaging in her backpack.

The minotaur stood ten feet tall and was covered in fur like dead brown grass. Its twisted horns sprouted from its forehead like dead trees clinging to a mountaintop. The two shorter elves pinned the minotaur to the cold metal ax with spears. The spears made deep gashes across the minotaur’s torso when it struggled with the strength of ten men.

“You’re hurting it!” said Aria.

The tallest of the three elves scoffed. “Who cares? Look what it did to my cute little gnome!”

One of the gnomes lay on the grass with his head split open. A green, rocky brain rest coldly in its skull. The second gnome held the brain in place with one hand while gesturing to Septem with the other.

Septem reached into his dress for gnomish surgical implements. “All will be well, Octoginta Tres. Merely a cranial fracture.” Septem sat to tend to the fallen gnome’s exposed brain.

“See? He’s fine,” said Aria. “Get off that minotaur, these are human lands!”

The tallest elf’s eyes glittered like emeralds, and her skin sparkled; so-called “high elves” bathed in gold dust if they could afford it. Her beehive hairdo added a foot to her height. She wore a long dress which no doubt concealed platform shoes, and lace wings which made her seem to float. Nonetheless she stood five-foot-eight, about seven inches shorter than Aria. “Gosh, if it’s not Aria Twine! It’s me, Stephanie! Are you the farmer trading us imps?”

“Not traded yet, Steph.” Aria dropped her backpack on the grass. “Tell your shorties to let the minotaur go.”

“Hmm, I don’t know, Aria,” said Stephanie, “under what jurisdiction?”

“You can’t steal game-pieces from human land,” said Aria. “He belongs to us. And you’re hurting him!”

Stephanie stroked her tall hairdo. “Hm… Shorties, let the beast go.”

The shorter elves—almost four feet tall—lowered their spears.

The minotaur’s gasps filled lungs the size of barrels. Its arms, packed with muscles like stacked melons, lifted three-fingered hands to rub the wounds on its chest and stomach.

“Let’s get something on those cuts,” said Aria.

Its ox-head turned on her. “Raaugh!”

“Hey! Easy, now! I’m here to—”

Its hooves stomped the grass.

It fled into the forest.

“Oh, what a shame,” said Stephanie. “We’ll have to go after it.”

Aria scowled. “You’ve done enough damage here.” The shorties looked to Stephanie, who shook her sleeves to the trees. The shorties took off after the beast, spears at the ready. “You’re out of line, Steph!”

Stephanie covered her mouth with her sleeve to hide a fake laugh. “Perhaps the gnomes have a different idea?”

Octoginta Tres was only distinguishable by his bandaged head-wound, and Septem Dicem by his goggles. Otherwise the gnomes were identical. “The high elf is correct,” said Septem. “An escaped game-piece belongs to no one. As you allowed the minotaur to flee, Aria, you relinquished humanity’s jurisdiction. The elves have the right to chase it and claim it.”

Stephanie giggled. “There you go, Twine. Perhaps you’ve forgotten the finer points of table-war?”

Aria picked up her backpack. “I challenge you for the minotaur.”

“The minotaur is already mine, dear. And besides,” smirked the elf, “your own game-piece is dead, isn’t it? That means you can’t command!” Aria grit her teeth. Stephanie coyly held her chin. “Who killed you, again? I can’t seem to remember.”

“You did,” Aria admitted, “but our match doesn’t need to be official. And I have something you want. I’m not ordering dragon fodder for nothing. I’ll wager my dragonling for the minotaur.”

Stephanie beamed. “Why, Aria, you just had to ask politely! Gnomes, would you care to referee?”

The three gnomes stood. After joining hands in a triangle, their fingers tapped messages in the same gnomish language written on brass cards. Septem nodded. “That is acceptable.”

Stephanie clapped. “Let’s set up a board!”

Stephenie’s tower of brass cards threatened to topple. Octoginta ran his fingers over each card apparently oblivious to his bandaged head-wound.

Aria had only a few brass cards. After Septem inspected them, he helped the third gnome prepare the table.

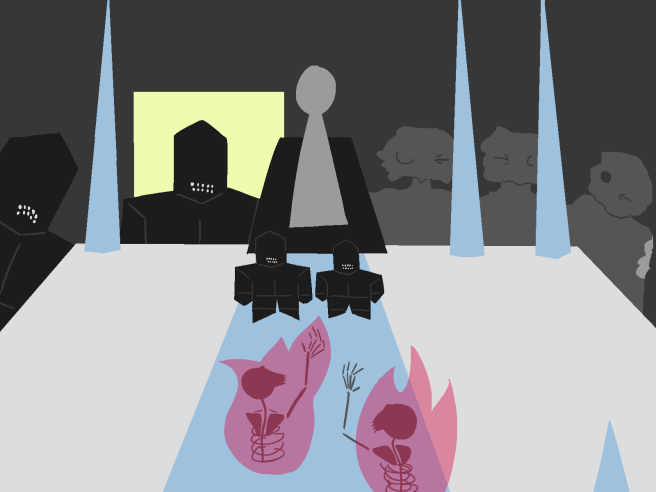

The table the elves had brought with them was sub-standard size, only five feet across and ten feet long. Stephanie demanded they construct the elven capital, but that required a full board. Aria and the gnomes talked her down to a smaller map.

Aria had played on this map before; it was popular among hobbyists. Stephanie’s side featured a thick forest. Aria’s side held rolling hills. The two sides were divided by a wide river. Even for an unofficial battle, the gnomes detailed the table intricately and effortlessly. Special gnomish clay built up the features of the terrain. The gnomes’ precise fingers carved trees and even grass. Beads in shades of blue painted the river’s speed, separating rapids from gentle banks.

“It’s hardly a match if it doesn’t represent a real area.” Stephanie arranged silver figurines on her half of the table. Each one represented an elven soldier described by a brass card. “Do you have game-pieces, Aria?”

“Sure do.” She poured the contents of her backpack onto the grass. Besides medical supplies she brought for the minotaur, she carried five wooden figurines. “Whittled ‘em myself.”

“Aww, how rustic!” As the sun rose, the Great Ax’s shadow shortened. Stephanie cooled her delicate features with a broad fan. The fan must have cost a fortune, because it was decorated with seashells. Seafolk always charged exorbitantly. “I suppose when I killed you, your official figurines were confiscated? My figurines were made by the elven queen’s own smiths.”

Stephanie smirked when her gnomes brought another metal figurine: a giant squid, pulled from the depths of the ocean. “You must’ve made general,” said Aria, refusing Stephanie the satisfaction of seeing her expression sour. “That’s a powerful beast. Buy it from seafolk?”

“Commander, darling! I’m a commander. I have much more powerful monsters, but they don’t fit on this tiny board.”

“The elf-queen must be pretty desperate if you made commander.”

Stephanie blinked. “She’s a better judge of talent, perhaps, than you are. The dwarfs are preparing for war; we elves must protect ourselves.”

“Septem.” The gnome turned to Aria. “Can you make me a brass for my dragonling, Scales?”

“I have not inspected it, ma’am. You must use the generic ice-dragon brass instead of one customized to your creature.”

“Fine.” Aria gathered her five wooden figurines from the grass. First she placed the wooden figurine representing herself—or, the version of herself described by the wooden hobby card, as her official brass claimed she was dead. Her figurine, accurately tall and lanky, stood behind three wooden imps.

“Are you just using any old units lying around your farm?” Stephanie hid her mouth with her sleeves to snicker.

“Plus one.” Aria placed a wooden cockatrice on the front lines. Aria remembered wearing dark glasses for two years raising the creature from an egg. “When I sold this monster to the human military, they said it was too volatile for table-war. I got to keep its brass. You can read on the card, I keep the cockatrice blindfolded for safety.”

The elf had perhaps a hundred game-pieces, while Aria’s side of the table felt more barren with each figurine she set on the field.

“Here,” said Aria, “we’ll use this roll of medical tape for the dragonling.” She placed it atop a grassy hill.

Octoginta tugged Stephanie’s lace wing. “Hey! This is elven silk, gnome.”

Septem hopped off the board to hold hands with his wounded companion. “He says your army can’t fit on this map. You can use the giant squid or the army of elves, but using both would pack units too densely.”

“Fine.” The elf waved her hand over the board. “Aria, as you’re clearly outmatched, I leave the option to you.”

“Keep both.” Aria straightened her wooden figurines. “You’ll need them.”

Stephanie’s lower lip wavered. “You pompous—”

“I’m ready. Hurry up.”

“Is that really all you’ve got?” asked Stephanie. “Your biggest monster is a dragon barely months old! Your cockatrice has to be blindfolded or it petrifies its allies! You’ve even put your own game-piece on the board! Embarrassing.” Aria swallowed as Stephanie arranged the enormous squid-figurine’s horrible tentacles to infest the forest canopy; internal mechanisms allowed the figurine to be realistically puppeted. Hidden buttons controlled the squid’s beak and eyes. “It’s a tad one-sided, isn’t it?”

“I agree.” Aria brushed hair from her face. “You go first, to even the odds.”

Stephanie hid a grimace with a smirk. “All my elvish units march forward. My archers ready their bows.”

The three gnomes linked hands to communicate and calculate. Then they scrambled over the board. “Elves are not hindered by forest terrain,” said Septem. “They move unimpeded. Say when.”

The gnomes made the metal elf figurines march halfway to the river. In the dappled shade of the model trees, Aria saw the features of the figurines’ faces. These were no mass-produced generic figurines, but actual models of real elves down to their freckles and pointed ears. “Stop there,” said Stephanie. The gnomes halted the elves.

“My dragonling allows the imps and cockatrice to mount it,” said Aria.

Gnome fingers clacked together. “The dragonling is strong enough, and the cockatrice and imps are small and light enough, to perform the action requested. Because your own figurine is present on the table, Ms. Twine, your expertise in taming monsters keeps them from fighting each other.”

“My dragonling runs across the river.” She pointed to a specific spot on the board. The gnomes used white beads to show how the river froze under the dragon’s footsteps, forming a path. “Perfect,” said Aria.

Stephanie covered her mouth. “Your dragon is too young to use ice-breath, isn’t it?”

“Maybe.”

Stephanie looked at the roll of bandages. “Better safe than sorry, right? My army retreats to the forest.”

The gnomes moved the elven figurines. “Is that all?”

“Not yet.” Stephanie leaned over the table. “Have you ever fought a giant squid, Ms. Twine?”

“Nope.”

“Then you might not know, being born in the arctic deep, they’re impervious to the cold! My squid engulfs my men with its tentacles, protecting them from the dragon’s breath.” She moved the tentacles herself. “There.”

Aria nodded. “Of course I knew that.”

“Ah, a guest!” Stephanie clapped. Her shorties dragged a net behind them. The minotaur pushed his three-fingered hands against the net, grunting with animal pain. The shorties pinned the beast with their spears. Aria noticed blood trickling from the minotaur’s closed eye. “Put it aside. This game ends soon. My archers will use Ms. Twine’s beasts as target practice.”

“It’s my move.” Aria pointed to the imps. “My imps remove the cockatrice’s blindfold, and Scales leaps face-to-face with the squid.”

“…My squid shuts its eyes!” Stephanie pressed hidden buttons to make the squid’s figurine blink.

“That kind of squid doesn’t have eyelids,” said Aria. “Too bad whoever made your figurine didn’t know that.”

The gnomes conferred. “The squid has turned to stone.”

Stephanie frowned.

“My imps fly through the stone tentacles.”

“My archers fire! The rest defend themselves from the imps with knives!”

As the gnomes held hands in deliberation, Aria left her chair to inspect the minotaur. “Let it out of the net. It’s calmed down.”

“No! Keep it restrained,” said Stephanie.

“Then put away the spears. You’re hurting it.”

Septem cleared his throat. “The stone tentacles are wrapped too tightly to draw a bowstring or swing a knife. Only the imps may move freely.”

Stephanie bit her lip. Gnomes showed how the imp figurines massacred her army. “…I forfeit.” Stephanie flicked over an elvish archer. “Why would I want a smelly, brainless beast, anyway?”

“Hold still.” Aria stroked the minotaur’s dense, prickly hair. “Shh, shh, shh.”

“It can’t understand you, you know.” Stephanie admired Aria’s imps in their tiny wooden cage. “Shorties, bring me their brass.” The cages were cramped even for imps. The devilish Togdag and Piknik pulled the metal bars with crimson claws. Gumdrop looked forlornly at their netted apple tree. “Are we sure this one’s an imp?” Stephanie stuck a finger into the cage to prod Gumdrop’s dragonfly wings. “It looks more like a fairy—Aaaugh!”

Gumdrop snickered as Stephanie clutched her chipped fingernail. “We’ll miss you, Twine!”

“Keep out of trouble, Gumdrop.” As the minotaur slept, Aria wrapped an eye-patch around its head. The shorties had injured its right eye; it would never see properly again. “Shh, shh, shh. It’s okay.” She poured clear liquid over the minotaur’s wounded chest. The sleeping beast grumbled at its stinging cuts. “You must be scared, so far from home. You’ll make plenty of friends when I sell you to the army.”

The shorties rolled barrels from the elven wagon. There were twenty barrels in all. “Your dragon fodder is ready,” said Stephanie. “You know, Aria, if you knew what was best for you, you could live in elven lands. You could help tame that giant squid. You could even be royalty.”

“I wanna be royalty because I’m awesome, not because I’m taller than you.”

Stephanie bared pearly teeth. “Come, shorties.” One shorty pushed the wagon from behind while the other pulled it from the front. “We’ll be back in elven lands within a week if you trudge fast enough.”

“Take care, dear,” said Aria.

Next Chapter

Commentary